|

Email: vern@cres.org — Box 45414, Kansas City, MO 64171-8414 |

|

|

OF CURRENT INTEREST Thanks for Noticing, 2nd edition Artificial Intelligence and the Soul Religion and Politics Alvin Brooks Memoir How Vern discovered Beethoven KU's Integrated Humanities Program How a Heretic Worships That Fountain in Mill Creek Park

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Scholars who

have initmated, though not developed, this research program are cited here.

COPYRIGHT 2005, 2020 Vern Barnet at CRES, Box 45414,

Kansas City, MO 64171

This chart may be reproduced without charge by

educational and non-profit organizations

so long as credit and contact information is included.

Please inform us of your intent to use. Thank you.

|

Share

the wisdom

of the world's spiritual traditions

NATURE is to be respected, more than controlled; it is a process which includes us, not a product external to us to be used or disposed of. Our proper attitude toward nature is awe, not utility. WHO WE ARE is deeper than we appear to be: this means our acts should proceed beyond convention, spontaneously and responsibly from duty and compassion, without ultimate attachment to their results. THE FLOW OF HISTORY toward justice is possible when persons in community govern themselves less by profit and more by the covenant of service. Those disempowered

by a secular age may, through the varied struggles, show THE IMPULSE

TOWARD

THE SACRED in fresh ways. OIL is an example of how the three crises of our time are interwoven with each other.

|

|

IN FURTHERING INTERFAITH UNDERSTANDING CRES may be the most connected interfaith effort in Kansas City, and the only one wedding academic competence with practical activities, but many groups are involved one way or another in promoting interfaith understanding. An increasing number of organizations bring interfaith awareness to their work. For a list, please see our report,KC Interfaith Opportunities, and let us know about the groups we missed. And you as an individual, you can encourage America’s tradition of pluralism by

*

supporting these organizations, Getting Started Doing Interfaith Stuff SELECT RESOURCES Basic Book

Locally

http://www.cres.org/pubs/primers.htm http://www.cres.org/pubs/guidelines.htm http://www.cres.org/pubs/WorldReligsPiecesOrPattern.htm

|

|

|

|

|

| 2026

Jan 22.-- We have been informed that the IRS has revoked our non-profit

status because we did not file a 990 for three years. We understood

that an exempt organization is not required to file a 990 if its income

is less that $50,000 a year. We are checking into this. Thank you for

your patience. CRES is a 501(c)(3) charity as determined by the IRS in its 1985 July 17 letter. Our legal name is the World Faiths Center for Religious Experience and Study and our tax ID number is 48-0953375. CRES, with its scholarly capacities and practical networking, has been central to the development of interfaith work in Kansas City since 1985 and has been nationally recognized by media, the academy, and civic and religious honors. For many years the Kansas City Interfaith Council was a program of CRES which organized it in 1989. Because of our professional volunteer staff, your gift to CRES provides an enormous "bang for the buck."

|

For on-line giving, you may use PayPal: |

#illusion

#illusion

|

Advice for Interfaith Activities

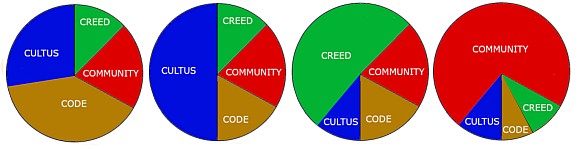

With Caveats for the Study of Religion © 2024 Vern Barnet, Kansas City, MO Everyone is free to use this material provided an acknowlegment is included. 1. “Religion” as often understood today developed from the Reformation’s distinction between secular and church domains, and from the West’s Enlightenment and Colonial categories of thought. Many “religions” don’t even have a word that corresponds to the way we often use “religion.” Underway is, to my mind, a lamentable process by which immigrants from non-Western traditions learn to understand their own traditions in Western categories of thought, a process which depletes the totality of the human experience with the sacred. Other processes also clarify, distort, and, in other ways, change the meaning of "religion." 2. Religions don’t differ from each other so much by offering different answers to the similar questions as by exploring different questions. Religions are more like different games and sports (chess, baseball, charades, tennis, swimming), with different rules, scoring, and outcomes, rather than like a football league with different teams playing each other. See Problems Comparing Faiths here. 3. Religions change throughout history and may vary by locale. 4. Religions are influenced by one another and sometimes incorporate elements from each other. 5. Within a single tradition, many variations are common. One Hindu should not be made to represent all Hindus. (“Hinduism” itself is a colonial invention.) 6. Boundaries around religions vary: some tight, some porous. 7. Even religions that emphasize theoretical (conceptual, catechetical, doctrinal) concerns retain elements of the earlier unitive (mystical, "peak" experiences), enactive (ritual), and narrative (story) developments. 8. Scholars who seek to identify components or dimensions of religions sometimes use the scheme of 4 C's: Creed (concepts or "beliefs"), Code (rules, moral expectations), Cultus (ritual practices), and Community (informal and institutional shapes and boundaries of adherents relating to one another).  Examples

of the different importance the four dimensions have in various faiths.

8a. Most religious are not as focused on "beliefs" as much as many Christians. It is sad that when folks of a non-Christian faith respond to questions from Christians, or seek to explain themselves to Christians, the discourse is often about beliefs, with the unconscious distortion of the faith. For example, highlighting the fact that most Jews do not accept Jesus as the Messiah misses the fact that traditionally being Jewish depends on having a Jewish mother (or conversion), which is centered not so much by belief as by belonging to a community. Asking whether a Zen Buddhist believes one will see family in heaven is absurd since the Zen Buddhist goal is extinction of the notion of the self. 9. A useful way to think about religions is to ask of them, * What is sacred? -- which can be phrased in many ways such as * What gives meaning to life? * What is the utimate source of value? * What guides your life when you are most aware? 9a. Applying the “What is sacred?” question can lead to a way of gouping the world's reigions into three main “families,” depending on where they find the sacred: roughly, with lots of qualifications and some exceptions: Primal traditions typically locate the sacred in the realm of nature, Asian practices typically focus on inner awareness, and the Monotheistic heritage typically finds the sacred (God) revealed through the history of covenanted community, as charted here and above. Examples of scholars who, in various ways, have classified the world's faiths in similar ways appear here. 9b. Of course within each family, religions have degrees of distinction, as in the second century, Christianity gradually became what we now consider a distinct religion, separate from Judaism and other Hellenistic cults, though influenced by them. Christianity, like all faiths, continues to evolve. Stephen Prothero's approach -- asking “what is the problem each faith seeks to answer?” -- can illuminate such distinctions. To illustrate with the three most familiar monotheistic faiths: the problem in Judaism is exile from God; the solutionis to keep God's commandments. Christianity's problem is sin; the solution is salvation through Jesus Christ. In Inslam, the problem is the sense of self-sufficiency; the solution is the submission to will of God. Whether Prothero has it exactly right or not, the chracter of each tradition is illuminated by comparing them in broad strokes and seeing the distictions. QUESTIONS

#questions

10. In ordinary human-to-human neighborliness, asking questions such as the following often may be more likely to build religionships than asking abstract questions about specific beliefs, such as "Do you think Jesus was crucified, died, and was bodily resurrected?" a. Can you tell me a story when the universe seemed to make sense to you or when you were overcome with a sense of awe? What experiences have you had that point to the ultimate source of life’s meaning for you? Have you ever seen a painting or heard music or walked on the beach or in a forest or played sports or seen a sunrise or learned about science or worked a math problem or held a child or made love when you felt lifted out beyond your ordinary sense of self?

10a. The scholarly study of religion is multivalent -- more than the

mere identification and accumulation of facts. https://cres.org/pubs/guidelines.htm #scholars Scholars have classified religions in many ways, creating various categories, and while Vern will focus on one of three common categories, you might want to know what the three are. Bainton, for example, presents three accents in the world faiths this way [I have colored the original text]: "Religions of nature see God in the surrounding universe; for example, in the orderly course of the heavenly bodies, or more frequently in the recurring cycle of the withering and resurgence of vegetation. This cycle is interpreted as the dying and rising of a god in whose experience the devotee may share through various ritual acts and may thus also become divine and immortal. For such a religion, the past is not important, for the cycle of the seasons is the same one year as the next. "Religions of contemplation, at the other extreme, regard the physical world as an impediment to the spirit, which, abstracted from the things of sense, must rise by contemplation to union with the divine. The sense of time itself is to be transcended, so that here again history is of no import. "But religions of history, like Judaism, discover God “in his mighty acts among the children of men.” Such a religion is a compound of memory and hope. It looks backward to what God has already done. The feasts of Judaism are chiefly commemorative: Passover recalls the deliverance of the Jews from bondage in Egypt; Purim, Esther’s triumph over Haman, who sought to destroy the Jews in the days of King Ahasuerus; and Hanukkah, the purification of the Temple after its desecration by Antiochus Epiphanes. And this religion looks forward with faith; remembrance is a reminder that God will not forsake his own. The faith of Judaism was anchored in the belief that God was bound to his people by a covenant, at times renewed and enlarged."

—Ronald H Bainton, Christendom, pages

3-4

For the CRES charted overview of world religions and what is sacred to them, click here. This way of looking at religions of the world is presented in greater detail elsewhere, such as in The Essential Guide to Religious Traditions and Spirituality for Health Care Providers, edited by Steven Jeffers, Michael Nelson, Vern Barnet, Michael Brannigan, Radcliffe, 2013 (p12-16). Suggestions of this scheme can be found in Eliade’s 1957/1959 The Sacred and the Profane, where he discusses cosmic, personal, and social contexts (p93-94), and the “individual, social, and cosmic” (p170). As noted above, in Roland Bainton’s 1964/1966 Christendom (Vol 1, p3-4), we find “Judaism is a religion of history and as such it may be contrasted with religions of nature and religions of contemplation. In Huston Smith’s 2005 The Soul of Christianity, he says that “‘becoming God’ happens individually, communally, and cosmically” (p124). Sociologist Robert Bellah’s 2011 Religion in Human Evolution (p175) notes that meaning obtains in “cosmos, society, and self”; this triad appears in varying forms throughout the book, as for example where he claims that music is “related not only to inner reality but to cosmic and social reality as well” (p25), and that it can attune “the individual to social and cosmic order” (p26); he also uses the triad “soul, society, and the cosmos” (p27). He does not relate these terms to the triad of Primal, Asian, and Monotheistic faiths; rather be believes that “Both tribal and archaic religions are ‘cosmological,’ in that supernature, nature, and society were all fused in a single cosmos” (p266). The Encounter World Religions Centre in Toronto, the Balance, Indian, and Middle Eastern traditions; and Robert Arkinson's three categories of indigenous, Dharmic, and Abrahamic religions in The Story of Our Time: From Duality to Interconnectedness to Oneness, 2017. #EckPluralism Diana Eck on

Pluralism

The plurality of religious traditions and cultures has come to characterize every part of the world today. But what is pluralism? Here are four points to begin our thinking: First, pluralism is not diversity alone, but the energetic engagement with diversity. Diversity can and has meant the creation of religious ghettoes with little traffic between or among them. Today, religious diversity is a given, but pluralism is not a given; it is an achievement. Mere diversity without real encounter and relationship will yield increasing tensions in our societies. Second, pluralism is not just tolerance, but the active seeking of understanding across lines of difference. Tolerance is a necessary public virtue, but it does not require Christians and Muslims, Hindus, Jews, and ardent secularists to know anything about one another. Tolerance is too thin a foundation for a world of religious difference and proximity. It does nothing to remove our ignorance of one another, and leaves in place the stereotype, the half-truth, the fears that underlie old patterns of division and violence. In the world in which we live today, our ignorance of one another will be increasingly costly. Third, pluralism is not relativism, but the encounter of commitments. The new paradigm of pluralism does not require us to leave our identities and our commitments behind, for pluralism is the encounter of commitments. It means holding our deepest differences, even our religious differences, not in isolation, but in relationship to one another. Fourth, pluralism is based on dialogue. The language of pluralism is that of dialogue and encounter, give and take, criticism and selfcriticism. Dialogue means both speaking and listening, and that process reveals both common understandings and real differences. Dialogue does not mean everyone at the “table” will agree with one another. Pluralism involves the commitment to being at the table — with one’s commitments. #Differences DIFFERENCES

or SIMILARITIES?

At the nation's first interfaith Academies, David Nelson spoke about his love of religious pluralism. His five points about interfaith conversations and activities can be found here. The question often arises in interfaith contexts -- Shouldn't we focus more on what we have in common, what we share, than on our differences? Similarities bring us together; differences divide us. "If everyone were cast in

the same mould,

there would be no such thing as beauty." --Charles Darwin, The Descent of Man, ch 19, 1871. My view is three-fold: 1. We are all alike -- and we are all different. To neglect either part of this paradox is to neglect our humanity. 2. Insofar as we are all alike, what do I have to learn? 3. Seeing differences as gifts may be a more effective frame of mind when we encounter differences because the differences, not similarities, at such moments are more obvious to us as our initial focus. When differences are welcomed, they do not divide -- they enrich. Focusing on similarities keep us from truly acknowledging the full personhood of those we meet and deprives us of expanding ourselves. A narrow focus on how we are alike hinders our genuine acknowledgment of their unique personhood. The focus on similarity does not remove the subconscious fear of difference; the fear of those outside our closest 150 friends and acquaintances must be positively replaced with anticipation of a new relationship, a novel idea, a fresh way of seeing things. Many studies in many kinds of situations, especially in business, show that groups of diverse people can access the world in a variety of ways and are therefore better at solving many problems. Differences, when welcomed, enrich the group's collective experience and foster a more vibrant and inclusive environment. Embracing differences as gifts can enhance our interactions, broaden our understanding, and contribute to the success of our communities. Differences are gifts. As we offer and receive them, the exchange makes our lives more vibrant and whole. Vern

Barnet

|

|

April 13, 2014, and again February 22, 2017 can make you commit atrocities. April 13, 2014 at the Jewish

Community Campus and Village Shalom in Overland Park, Kansas. William

Corporon, 69, his grandson Reat Underwood, 14, and Terri LaManno, 53,

were gunned down by a self-described anti-Semite. Mahnaz Shabbir 2005 report |