Additional items are noted here. Kansas City Magazine bio salute: Alvin Brooks, 2024 First Place Winner, 2022 Thorpe Menn Literary Excellence Award JCRB/AJC Henry Bloch Human Relations Award, 2022 Report on the 90th Birthday Party Greater Kansas City Chamber of Commerce "Kansas Citian of the Year," 2019 Kansas City Star BioSketch on release of the book, 2021 Feb 21 Rockhurst University establishing the Alvin Brooks Center for Faith-Justice Brooks on KCUR's A People's History of Kansas City Brooks -- A Black History Month video, YouTube 2 min 31 sec |

| #BrooksMemoir |

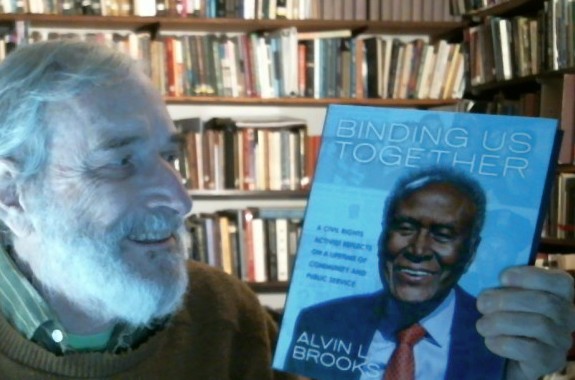

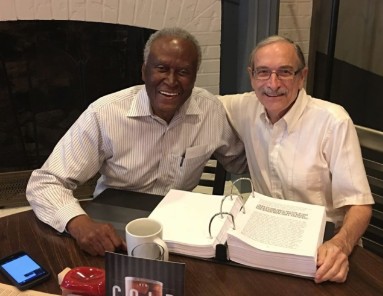

Vern with a pre-publication copy 2021 Jan 22; the publication date was Feb 23. Vern was developmental editor for the Andrews McMeel book, distributed by Simon & Schuster. Link to Kansas City Star article

A Reader's Unsolicited Comment I just finished Binding Us Together and

I love it. It's Kansas City history arriving at a time when more of us

systematically-biased white folks are beginning to realize the extent of

our culture's caste system. Basically, often we were (and are) biased

and didn't know it.

Steve Nicely

retired Kansas City Star writer, photographer, columnist, and editor -------------- Another Reader's Unsolicited Comment When I first heard about Alvin L. Brooks's new bookBinding Us Together I knew I wanted to read it. Mr. Brooks has always been, in my opinion, one of our most respected leaders in our community. Since I am an avid user of Audible.com, I hoped that I could get his book in Audio format. I was delighted to find I could listen to the book on Audible.com -- and even more excited that it was read by Mr. Brooks. His voice has always been distinctive to me and I have found it easy to recognize his soft and positive message. To write a book is an undertaking that few would attempt. To write on Racism and the challenging and powerful impact that is had on the writer as a small child life is amazing. Mr. Brooks has a lifetime of experiences that would make any reader (or listener) both laugh and cry. Mr. Brooks reading his audio book brings alive even more his emotions on many of the events in his life. Using many personal events he helps us understand both his years to tolerating and learning from family and his life experiences. He learned to use positive leadership skills to develop solutions to address Racism as he demonstrate that it is not words but actions that cause change. Whether you read or listen to this important and insightful book I think you will join me in rejoicing that Mr. Brooks has committed his whole life to actions that will help “Bind Us Together” !!! Dale R. Herrick

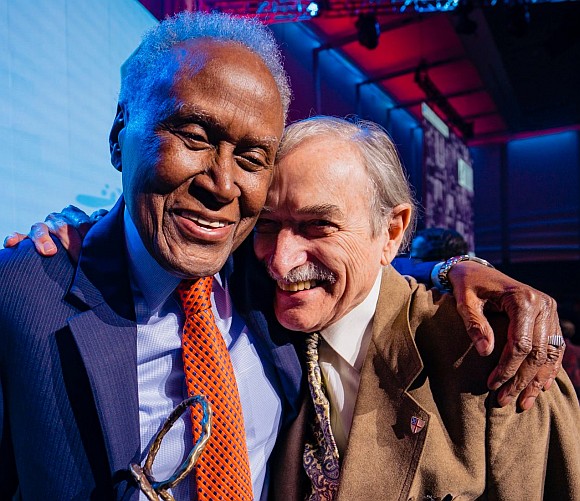

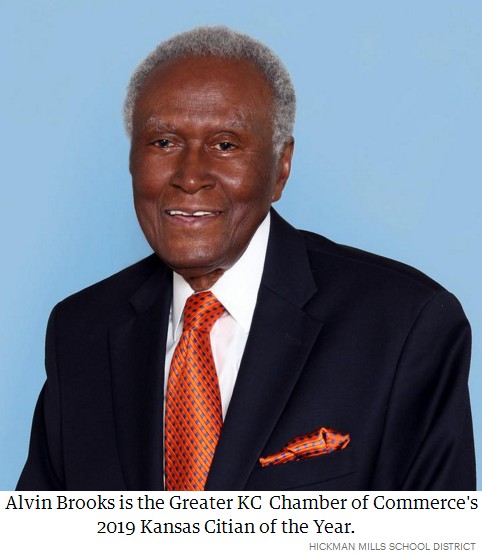

#BrooksBarnetChamber2019

Liberty, MO

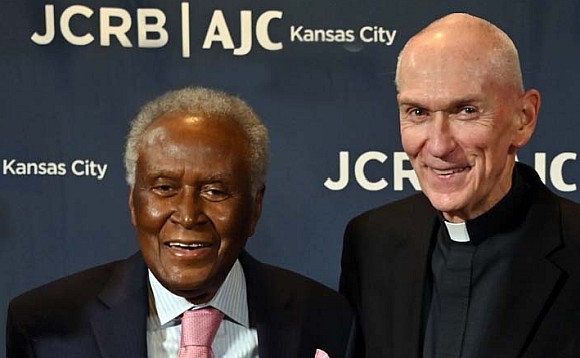

Vern congratulates Al after he was introduced as "Kansas Citian of the Year" at the greater Kansas City Chamber of Commerce annual dinner in November 26, 2019. For a report on the dinner with civic and business leaders and 2,000 guests, use this link [Photo credit: Kyle Rivas]

|

|

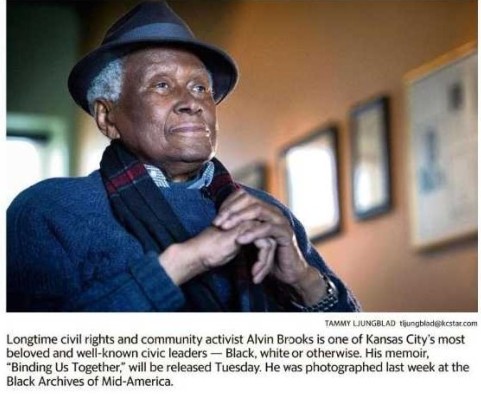

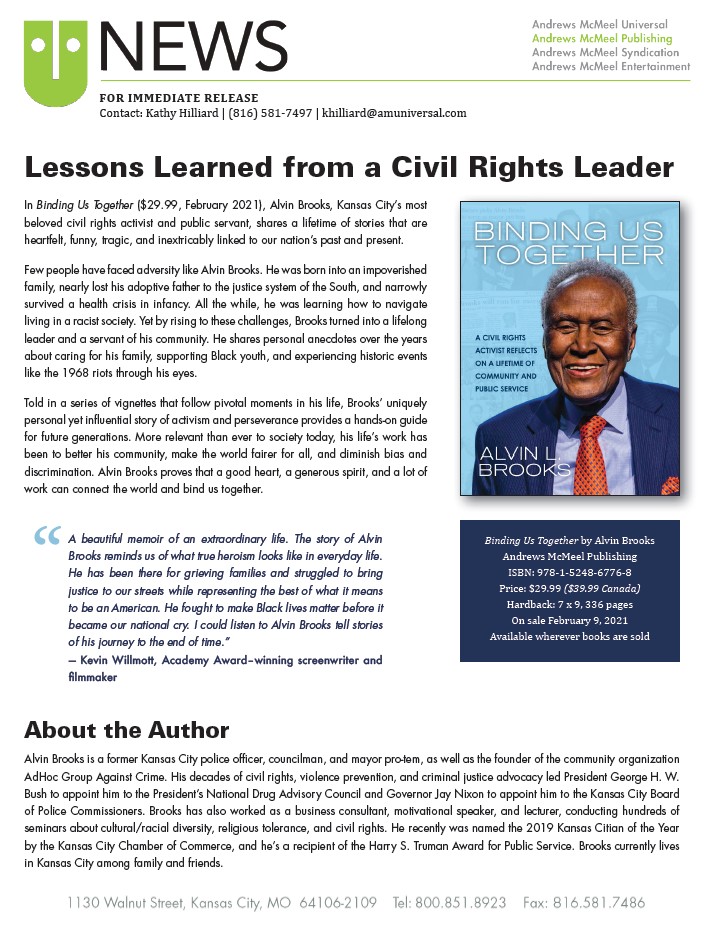

A love story imperiled by racism, saved by service February 21, 2021 | The Kansas City Star | Mar? Rose Williams Editor’s note: During the month of February, in honor of Black History Month and the vibrant Black community in Kansas City, The Star will feature profiles of Black Kansas Citians by telling their stories and highlighting their businesses, causes, and passions  In the years since he arrived as an infant with a Black couple he thought were his biological parents, Brooks, 88, has become one of Kansas City’s most beloved and well-known civic leaders — Black, white or otherwise. “That man loves Kansas City,” said Carrie Brooks-Brown, the second of his five daughters. ”He thinks it is the greatest city in the world.” When it comes to his greatest loves, she said, “It’s God, family and Kansas City. That’s the order he puts them in.” When it comes to his legacy, the list goes on and on: community engagement, social justice, civil rights, education equity, criminal justice reform — he’s had a hand in every bit of it. Over four hours of Zoom interviews with The Star, Brooks, sitting at his kitchen table, recounted a litany of stories — humorous and heartfelt — that document his life and its intersection with some of Kansas City’s most notable moments. From his 10 years as one of the few Black officers on Kansas City’s police force during the 1960s to launching a citywide crime prevention organization to eventually becoming mayor pro tem, Brooks has led a life of service to his city, and he’s not done yet. In 1989, President George H.W. Bush named Brooks one of America’s 1,000 Points of Light. In 2016 he received the Harry S. Truman Public Service Award and in 2019 the Greater Kansas City Chamber of Commerce named Brooks Kansas Citian of the Year. Brooks has turned down at least a handful of job offers in other cities. Nothing, he said, could pull him away. “This is home,” he said. But it didn’t start here. “I was born in North Little Rock, Arkansas, May 3, 1932,” Brooks said. Brooks rattles off dates that way, as if they were as familiar as reciting his own birthday. “He remembers everything,” said Estelle Brooks, his oldest daughter. But it also could have been that those dates were fresh in his mind, given that Brooks recently finished his memoir, “Binding Us Together,” set for release Tuesday by Kansas City-based Andrews McMeel Publishing. “The story of Alvin Brooks reminds us of what true heroism looks like in everyday life,” Academy Award-winning screenwriter and University of Kansas film professor Kevin Willmott wrote in an endorsement of the book. “He fought to make Black lives matter before it became our national cry.” The root of the problem Cluster and Estelle Brooks weren’t his biological parents, but they were the only ones Brooks knew for about a quarter of his life. His actual mother was 14 and unmarried when she had him, a scandal back then. So while pregnant, she left her Florida hometown to stay with an older sister in Arkansas. A pregnant teen didn’t sit well there either, Brooks said. So under pressure from family, she moved across the street to stay with the Brooks family. After Brooks was born, his mama left him there. “I didn’t know that the Brookses weren’t my real parents until 1954,” Brooks said. “I was 22 years old when my biological mother found me. Nine years later, in 1963, she found my biological father, and the three of us became very close.” He didn’t know until writing his book that Estelle and Cluster Brooks had never actually adopted him. They saved his life though. As a baby, Brooks had a mysterious ailment and vomited everything he ate. “I was dying of malnutrition,” he said. A local doctor suggested the baby be fed goat’s milk. The family bought a goat. The milk worked. Brooks was less than a year old when they all fled Arkansas. Cluster Brooks was known for making “the best moonshine in Pulaski County, Arkansas.” During an argument over whether that was indeed true, Cluster, brandishing his Winchester rifle, shot and killed a white man. The penalty for a Black man killing a white man in 1933 was certain death. A conversation with Brooks means listening to a host of old sayings, mama-saids and story after story. He clearly loved retelling this one and smiled when he got to the end of it. The story Brooks heard growing up was that his dad, awaiting his fate, had his mom go talk with the judge. His dad told her to chew on a piece of High John the Conquerer root and at the right moment spew some of the muddy-brown juice on the judge. A sneeze did the trick. In folklore, the root is named for a Black slave whose spirit was never broken. It is said to bring luck. The judge told Cluster either he would die for his crime or he would leave the state of Arkansas for good. The family sold nearly everything they had, packed the rest along with Nannee, the white, pink-nosed Saanen goat, in Cluster’s Model A Ford and fled “under the cover of darkness,” Brooks said. “That’s how we got to Kansas City. And I have been here ever since.” Education a priority Brooks said his parents always told him, “Get an education, son, get an education. And they used to say white folks can take anything away from you if you’ve got it in your hands, but if you’ve got it in your head they can’t take it away from you. And you had to be more educated than the previous generation.” His family first settled in the Leeds area near Arrowhead Stadium, “a poor Black area where houses had no running water inside,” Brooks recalled. When he was 9 or 10, his parents rented a house “in a poor white area off of Linwood and Brighton.” The Brooks family was poor too. “We didn’t have electricity,” Brooks said. They did raise some farm animals, and Brooks remembers selling eggs and goat’s milk to his white neighbors, “as long as I took care of the chickens.” When they first moved in, fights with the neighborhood boys were a regular occurrence. Later they became close friends. “We got into trouble together. Well, not bad trouble,” Brooks said. “Good trouble,” like the times his friends would buy him food at the whites-only lunch counter and then coax him to sit down with them and eat fast before the waitress shooed them all out for eating with a Black kid. They couldn’t go to school together either. His friends went to the all-white school nearby. “I had to walk all the way to Dunbar Elementary School, “where the Black kids went,” Brooks said. He would later attend R. T. Coles Vocational Junior High School and then Lincoln High School. “At that time there were 10 high schools in Kansas City, eight for white kids and two for Black.” His mother died in 1950, “the year I graduated from high school,” he recalled. He later attended Lincoln Junior College, “the Black junior college, which was on the third floor of Lincoln High School. Because we couldn’t go to the white junior college.” Brooks was already married by that time. He was 18, and in his senior year, when he wed Carol LaVern Rich. The couple had six children and were married 63 years before she died in 2013. His son, Ronall Brooks, a U.S. Air Force veteran, died in 2003 after years of substance abuse. Brooks was a family man, his daughters said, but “Mom was the orchestrator of everybody’s calendar and kept him informed so he knew just when to step in on something,” said daughter Roslind Wesley speaking in an online interview along with her four sisters. “Dad had the weirdest punishments,” but most of the time he would lecture, sometimes close to an hour. Brooks-Brown preferred a spanking. One time two sisters were fighting. “Dad made them sit on the steps and hug for an hour,” she said. Alvin Brooks2 021921 tll 013F.jpgAlvin Brooks with his beloved wife, Carol and their family. The pair were married for 63 years before she died in 2013. They had six children, 17 grandchildren, 30 great-grandchildren and 11 great-great-grandchildren. A community policeman But most of the time, they said, their dad was “super busy.” People would call their house all hours, day and night, asking for his help with something going on in the city or their lives. “Dad would get up and go,“said Estelle Brooks, the oldest sister. It didn’t matter whether it was a local dignitary or the grieving mother of a son accused of murder. “Alvin deliberately takes up the pain of others,” the Rev. Wallace Hartsfield, who died last year, told The Star in 2003. “He doesn’t have to do that. He has his own pain. But he has surrendered his life for others, and that is the secret to his strength.” “It was a part of what I felt I had to do,” Brooks said. “My wife would say, ‘You don’t belong to us, you belong to the community. Just make sure the checks are mailed here.’” His daughters, now all professionals and running their own businesses, said they learned their work ethic from him. Out of high school, Brooks had wanted to be a pharmacist, until one of the three Black pharmacists serving the Black community told him no white-owned pharmacy in town would ever hire a Black man. He wasn’t sure the city could support another Black-owned pharmacy. Brooks went to Lincoln Business College instead. Before he could graduate, the school was shuttered by the federal government for some wrongdoings. All the school records Brooks needed to prove he had the education were confiscated, gone. He had to start over. He worked three years as a janitor — one of the only jobs a Black man could get — at Ford Motor Co. Assembly Plant. He then got hired as one of 16 Black officers on the city’s police force. When he shared his career choice with his dad, “He said, ‘Son, why you want to do that? You know how they treat us.’ But my thought was that I was gonna be a better cop,” Brooks said. Black officers were only allowed to patrol in Black neighborhoods until 1958, when a new chief, Bernard C. Brannon, sent a few to patrol the city’s Northeast Area, where many European immigrants lived. One night Brooks was called to Northeast High School on a report of a body hanging from the flagpole. Turns out, when officers pulled the figure down, “it was a mannequin splattered with ketchup with a note pinned on it that said ‘Al Brooks, nigger go home.’” Brooks said they never found out who did it. But his fellow officers carried the mannequin back to the station and propped it up in a chair, where it stayed for days. Brooks found no humor in it and one night sneaked back to the station and tossed it in a dumpster. Brooks, a detective in the gang unit, would face racism many times during his 10 years on the force. “I took the sergeant’s test and passed it three times. But I couldn’t get promoted,” he said. But he’s quick to say how much he’s seen change on the force over the years and was happy to see Darryl Fort? named the city’s first Black police chief in 2012 and, in 2018, the first Black sheriff of Jackson County. Brooks took the community policing approach to his job. “Everybody in town knew my dad and he knew them by name,” Brooks-Brown said. She remembers as a kid when she and her dad walked into a restaurant for burgers one evening and everyone in the place stared at them. “He asked them, ‘What’s going on here?’ and the lady behind the register pointed to this guy and said, ‘He’s trying to rob us,’” Brooks-Brown said. Her dad knew the man and scolded him, as a parent would a misbehaving child. She said the man handed her dad his gun, and Brooks walked him outside to the backseat of his car. “Dad took me home, then took that guy to the station.” But in 1964 Brooks left the police force for a job in student services in the Kansas City school district. He had long cultivated a relationship with the district. As a cop, he said, “I worked nights so during the day I’d put on my uniform and go over to the school and just sit and talk to the kids. People thought I was crazy. But all those kids knew me.” Brooks was there for them in 1968, when students erupted in unrest in the city streets after the April 4 assassination of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. “I was there on the steps of City Hall,” Brooks said. “I marched with about a thousand of those kids from 22nd and Vine all the way to City Hall.” The night before, Brooks had met with several school administrators, one of only three Black men in the room. He warned them that Kansas City, Kansas, schools were planning to close so students could mourn the death of the civil rights icon. If Kansas City stayed open, he said, “all hell would break loose.” No one listened, and the student protest went out of control when police deployed tear gas. Three days of riots ensued. Five Black men and a 16-year-old boy were shot and killed — four of them, perhaps all — by police. For the city and its people Brooks left the school district six weeks after the riots and became director of human relations in Kansas City government, a first for a Black person. It was a job he never really wanted. But the city manager wanted him. Others did not. At the time Brooks was chairman of the local chapter of the civil rights group Congress of Racial Equality (CORE). “They thought I was too radical. I’m arrogant. I took the job because they didn’t want me to have it,” Brooks said. “And friends told me to go take it because someone has to be a trailblazer over there.” Brooks and other city movers and shakers met regularly for meals at Mooney’s Restaurant, now gone, and talked about how to advance Black Kansas City. “We called it the Black city hall,” Brooks said. He was encouraged. And in 1972 he was appointed assistant city manager. As if the demands of city government weren’t time consuming enough, Brooks also went and got a master’s degree in sociology from the University of Missouri-Kansas City. His thesis on social organizing and social change would become the framework for his launching the Ad Hoc Group Against Crime in 1977. The crisis intervention and prevention group supports families affected by violence. Brooks was often among the first people at the scene of crimes, called by victims, perpetrators or their families, because they trusted him. Brooks stepped away from Ad Hoc in 2000 when the group merged with Project Neighborhood and changed its name to Move Up. He returned to lead the group again in 2008, until he retired in 2015. Retirement, for Brooks, doesn’t mean sit and relax. He had been appointed to the Board of Police Commissioners in 2010 and continued serving until 2017. And he’s currently serving out a four-year term on the Hickman Mills school board. People still call him when they get in trouble. But he doesn’t get up and go as often as he used to. Over the years he has intervened in more homicide investigations than he can count, “hundreds probably.” One crime though, more than any other, rattled this old tough detective to the core, the murder of “Precious Doe.” Three-year-old Erica Michelle Marie Green’s decapitated body was discovered on April 28, 2001, in a wooded area near 59th Street and Kensington Avenue. Her head was found nearby days later. She remained unidentified until May 5, 2005. Her mother, Michelle Johnson, and her stepfather, Harrell Johnson, were charged with her murder. Police said her stepfather had used a pair of hedge clippers to sever the child’s head after she had been beaten. He was sentenced to life without parole. Brooks led an effort to raise money to establish a park in the same area where Erica’s body was found. At the time, Brooks was a Kansas City councilman, a position he held from 1999-2003. He was mayor pro tem while former Mayor Kay Barnes was in office, 1999-2007. When her term ended, Brooks made a run for mayor and lost to Mark Funkhouser. “I was never meant to be mayor,” Brooks said. His role, he said, has always been “to try and bring people of all races together. To serve, to be a voice that helps our community our people, all our people.” Some call Brooks a Kansas City patriarch. A man of grace, dignity and strength who has literally helped raise and mentor many of the city’s Black leaders, including 3rd District Councilwoman Melissa Robinson and former Councilman Jermaine Reed. “Mr. Brooks has been like a father figure and grandfather figure to me from when I was really young to adulthood,” Reed said. Alvin Brooks2 021921 tll 087F.jpgWearing hats they purchased in Washington, D.C., Jermaine Reed, left, and Alvin Brooks shared a laugh as they reminisced over their trip to the nation’s capital in 2009 to watch the inauguration of President Barack Obama, America’s first Black president. Reed is a longtime friend and protege of Brooks. Reed said from the moment he saw Brooks being interviewed for his role at Ad Hoc, he has clung to his coattails. Brooks remembers Reed as a boy hanging out at Ad Hoc offices every day. Reed was there to learn from Brooks. “I wanted to do what he was doing,” Reed said. “He took me under his wing. He gave me sage advice, a level of tutelage I would never have gotten had it not been for him. His level of commitment to justice, fairness, equality and to change the face of our community is remarkable.” In 2009, Reed went with Brooks to Washington, D.C., for President Barack Obama’s inauguration. “I remember it was freezing. We had to walk a long way. Mr. Brooks didn’t complain one bit. Many African Americans thought they would never live to see another African American in the White House. And to be there that day with someone who has dedicated his life to civil rights is something I will never forget.” The two stood among the throngs of people in the cold listening to Obama speak. “I looked up at Mr. Brooks and tears were just streaming down his checks.” Brooks says he still has things to do yet and spends much of his time speaking to young people, encouraging them to continue unraveling threads of systemic racism woven into the fabric of the country. “Yeah, I’ve slowed down,” Brooks said. “But I haven’t stopped.” Alvin Brooks’ memoir, “Binding Us Together,” is set for release Feb. 23.

Author event Alvin Brooks will discuss his career and life

with Kansas City Mayor Quinton Lucas in a livestream event that launches

Brooks’ new autobiography, “Binding Us Together: A Civil Rights Activist

Reflects on a Lifetime of Community and Public Service,” 6:30 p.m. Feb.

23. For details and to RSVP, see kclibrary.org or rainydaybooks.com.

Other photo identifications: During a stop Thursday at the Black Archives of Mid-America, Alvin Brooks took a call from Carrie Brooks-Brown, one of his five daughters. Alvin Brooks as a child with his mother, Estelle Brooks. Alvin Brooks with his beloved wife, Carol and their family. The pair were married for 63 years before she died in 2013. They had six children, 17 grandchildren, 30 great-grandchildren and 11 great-great-grandchildren. Carlos Nelson Sr., president of Cascade Media Group, recorded a session with Alvin Brooks on his recollection of the 1951 floods that hit Kansas City for an upcoming documentary. In 2005, Alvin Brooks, then mayor pro tem, studied police renderings of Erica Green, known as “Precious Doe” until she was identified. That day, the prosecutor’s office announced that her mother was charged with second degree murder in Erica’s death. In 2009, Alvin Brooks traveled to

Washington, D.C., to witness Barack Obama, the nation’s first Black president,

take the oath of office.

|

Memoir update! August 3, 2020

BioVideo: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4aWxwuiWTnA Photos (one with Vern) and story of the 2019 Nov 26 event, click here. From the Kansas City Business Journal, 2019 November 27: Alvin Brooks, who has worked tirelessly for equality and against crime for decades, was honored as the 2019 Kansas Citian of the Year. The Greater Kansas City Chamber of Commerce named Brooks as the recipient of the award Tuesday, highlighting the chamber’s annual dinner. Chamber officials expected a crowd of as many as 1,800 for the event. Brooks, 87, was one of the first African Americans to serve in the Kansas City Police Department, starting as an officer and eventually serving on the Kansas City Police Board. He founded the Ad Hoc Group Against Crime, a nonprofit that works to make Kansas City neighborhoods safer by acting as a bridge between the community and the police. Brooks long has been a leading local civil rights leader. He directed the Kansas City Human Relations Department soon after race riots in 1968. He also has served as Kansas City’s first black assistant city manager, a City Council member (1999-2003) and unsuccessfully ran for mayor in 2007. He now serves on the board of the Hickman Mills School District. Former Mayor Kay Barnes, the 2018 Kansas Citian of the Year, presented the award to Brooks. He was mayor pro tem when Barnes was in office. The selection of a peacemaker as Kansas Citian of the Year was a fitting close to a chamber dinner celebrating a truce in the development Border War between Missouri and Kansas. The governors of the two states were scheduled to appear at the dinner. The annual dinner also serves as the official passing of the position of chamber chair. Carolyn Watley, vice president of community engagement for CBIZ Benefits ? Insurance Services, officially takes over as chairwoman on Nov. 1, succeeding JE Dunn Construction Co. CEO Gordon Lansford. -------------

|

For over three years, Vern has been working with Alvin L. Brooks to edit Al's Memoir. By August 1, 2020, the manuscript at 250,000 words, seemed complete enough to pass it on for the next stage in the publication process. During this time, Al was interviewed on KCUR for an hour portrait on air. Jen Chen summarized the appearance here.

Beyond Belief Web Extra | Kansas City Icon Alvin Brooks https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iW45d8YKeHY

Brooks was named the 2017 "Outstanding Native Kansas Citian of the Year" by The Native Sons and Daughters of Greater Kansas City.

Faith in KC: A conversation with Alvin Brooks

|

| #BrooksPhoto180809

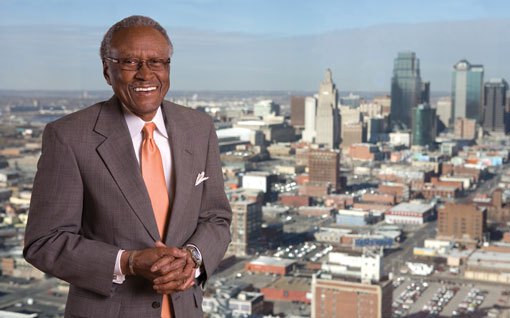

The Honorable Alvin Lee Brooks

Vern Barnet

RELEASE FROM COPYRIGHT expressly for Wikipedia and

all other uses

I hereby affirm that I, Vern Barnet, am the creator and sole owner of the exclusive copyright of the image shown above and have legal authority in my capacity to release the copyright of this work. I agree to publish the above-mentioned content under the free license: Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported and GNU Free Documentation License (unversioned, with no invariant sections, front-cover texts, or back-cover texts). I acknowledge that by doing so I grant anyone the right to use the work in a commercial product or otherwise, and to modify it according to their needs, provided that they abide by the terms of the license and any other applicable laws. I am aware that this agreement is not limited to Wikipedia or related sites. I am aware that I always retain copyright of my work, and retain the right to be attributed in accordance with the license chosen. Modifications others make to the work will not be claimed to have been made by me. I acknowledge that I cannot withdraw this agreement, and that the content may or may not be kept permanently on a Wikimedia project. Vern Barnet, Photographer

Appointed representative of the subject of the photo, the Honorable Alvin L Brooks, for this purpose 2018 August 9 Kansas City, MO This photograph was taken at the Plaza Branch of the Kansas City Public Library #Milestones MILESTONES IN THE LIFE OF ALVIN LEE BROOKS 1932 May 3 Alvin Lee Brooks

born, North Little Rock, AR

1968 May 27 Appointed first

Director of Human Relations Department, KC,

1977 AdHoc Group Against Crime formed The Kansas City Star Magazine, August 19, 1984, page 8-28 1989 Appointed to President’s National Drug Advisory Council for three years 1990 Named one of America’s “1000 Points of Light” by President G. H. W. Bush 1999 Elected 6th District

City Council Member, made Mayor Pro Tem

The Kansas City Star, March 28, 2007 2008 Re-energized AdHoc

2013 July 21 Carol Rich Brooks dies 2016 The City Council of the City of Kansas City, MO, declares May 3, 2016, as Alvin L. Brooks Day in its Resolution No. 160372 http://cityclerk.kcmo.org/LiveWeb/Documents/Document.aspx?q=ffbTlyJyJmLHh0gG%

2016 Brooks honored with the

Harry S. Truman Public Service Award -- The Kansas City Star, April 5,

2016

2FdDdqYMiprX16RtCfLIx1x4rP3IrIoaTWanlC8V35AP4F160QXvS6tcYc% 2FxRlduqHLHoGA%3D%3D

2021 The Brooks memoirs, Binding Us Together: A Civil Rights Activist Reflects in a Lifetime of Community and Public Service, is published by Andrews McMeel Kansas City Star, February 21, 2021,

page 1 and 10A

pages 19-36 for a comprehensive biographical sketch. Brooks appears in Tanner Colby's 2012 (Penguin)

book

#Rockhurst Alvin Brooks Center for Faith-Justice Tuesday, November 23, 2021 Jewish Community Relations Bureau | AJC 2021 Human Relations Event  Rockhurst University will honor Alvin Brooks, longtime Kansas City leader in social justice and civil rights, with the establishment of the Alvin Brooks Center for Faith-Justice on campus. The center will house many of the university’s faith-justice related efforts, including a chapel, mission and ministry programs, and diversity, equity and inclusion programs. Work has begun to raise funds for the center and to identify a location and construction and design partners. The Rev. Thomas B. Curran, S.J., president of Rockhurst University, announced the initiative at the Jewish Community Relations Bureau|AJC’s annual Human Relations event Nov. 18, where he was honored with the Henry W. Bloch Human Relations Award. The award recognizes “a person who has led by example, sought justice, and who embodies the Jewish mission of ‘repairing the world.’” In his acceptance remarks, Fr. Curran called Henry Bloch and Alvin Brooks true and genuine humanitarians. “To me they epitomize what it means to cooperate and co-labor with the gentle disposition of God’s providence to bring about ‘mishpat, tzedek,’ ‘justice in our time,’” Fr. Curran said. During the program, Rabbi Alan Londy from New Reform Temple moderated a panel discussion with Rockhurst University students Bridgette Berry, LC Coldiron, Zander Haddad, Alexandra Moss, Shaili Patel and Michael Sitti. The students all took Fr. Curran’s class on Catholic social teaching, where Rabbi Londy was a frequent guest. At the end of May, Fr. Curran will complete his 16th and final year as president of Rockhurst University. He announced in September that he would leave to have a sabbatical followed by his next assignment with the Society of Jesus, the Jesuit order of Roman Catholic priests of which he is a member. Kansas City Celebrates the 90th Birthday of Alvin Brooks

Rejoicing in who Mr Brooks is, and what he has done and is still doing, can lead us to use our own abilities and energies to recognize and uplift the dignity and glory of human diversity. Metropolitan Community College

Trustee Jermaine Reed, a longtime friend and mentee of Mr Brooks,

served as master of ceremonies. “It was a joy to spend the day

celebrating with so many of Mr Brooks’ friends and family, and an honor

to play a role in thanking him for all he has done for our city,” Reed

said. The inscription reads: "CRES gives thanks for Alvin L Brooks for his work as citizen and his career of public service locally and internationally celebrating religious pluralim and the dignity of the human spirit in compassion, justice, and leadership. Thanksgiving Sunday, November 23, 2002." It is not yet too late to plan to attend the 100th birthday party. [Portions of this report are adapted from a press release by the Metropolitan Community College. #ThorpeMenn Among twenty-six highly competitive nominations, congratulations to Al Brooks for his first place recognition for his book, Binding Us Together: A Civil Rights Activist Reflects on a Lifetime of Community and Public Service at a wonderful luncheon at the Woodneath Auditorium at the Story Center, Mid-Continent Public Library. Al especially noted John Dill, of blessed memory, who suggested the title for the book. In his acceptance remarks, Al told a humorous story occasioned by the remarks of the keynote speaker. Al has a story for every occasion! The Thorpe Menn Literary Excellence Award was established in 1979 by AAUW-KC to honor Thorpe Menn (1912-1979), long-time book editor of the Kansas City Star, who supported all aspects of Kansas City’s cultural life, especially authors and artists. This is the 44th year of the awards. Also recognized were Theresa Hupp and Steve Paul for their recent books. Lisa D Stewart, first place winner last year, was the keynote speaker. Mark Livengood, Story Center Director, welcomed everyone, along with AAUW KC President Corinne Mahaffet. Patty Cahill was the facilitator and Jane McClain was the story teller. Vern Barnet, developmental editor for Al's book, was delighted to join in the celebration. #JCRB_Bloch JCRB|AJC Annual Human Relations Event 2022 October 30 at the Sheraton-Crown Center Henry W Bloch Human Relations Award Honoree Alvin Brooks lifelong civil rights activist and civic leader "Justice, Justice shalt thou pursue" --Deuteronomy 16:20 use this JCRB|AJC link for information, sponsorship and tickets Brooks on KCUR's A People's History of Kansas City

Alvin Brooks is a public figure who has served as a bridge in Kansas City for decades. He was one of the city’s first Black police officers, an educator, a leader in the civil rights movement, a founder of Ad Hoc Group Against Crime and almost a Kansas City mayor. Yet few know about his personal life and the internal struggles he’s faced. KCUR’s Reginald David talks to Brooks about the moments in his life that shaped him and pushed him to fight for a better Kansas City. LISTEN 37:44 (after sonic introduction, after host introduction, after interviewer introduction) |