|

|

For reprint permissions, click here.

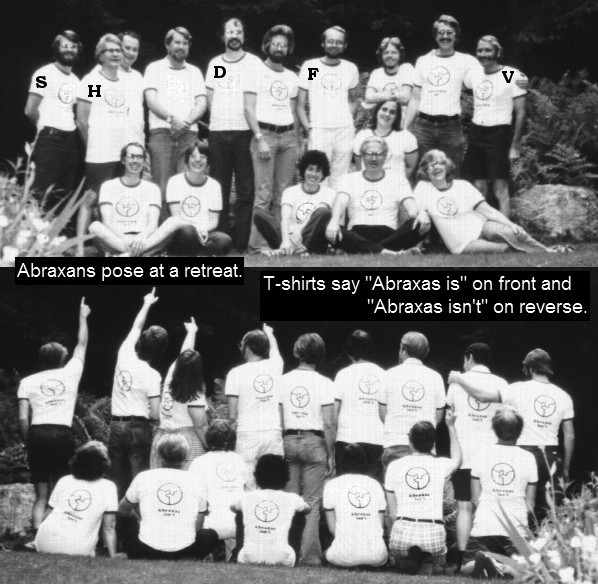

The T-shirts display the three-part "foot of Abraxas."

The Original Five (O.F.) Abraxans are identified with initials:

Stephan the Spare, Harry

the Holy, Duke the Dumb, Fred the Full, and Vern the Void.

| Vern the Void's Rant Vern the Void's New Rant |

| * |

| THEORY and LITURGY produced by Abraxas |

| Essay on Worship |

| scan: Matins |

| scan: Eucharist. Digitized Eucharist |

| scan: Compline |

| PDF: Unfinished Vespers. |

| scan: Rite of Ordering (public version). |

| PDF: Ritual for People who Hate Ritual -- Parish Liturgy |

| ** |

| OTHER DOCUMENTS |

| Worship Reader (under construction). |

| Historical Notes (under construction) and Chronicles of Abraxas |

| News Story of a Retreat |

| Vestments |

| Abraxas West and The Rite of Religion -- construction pending |

| ** |

| COMMENTARY and STUDIES ABOUT ABRAXAS |

| Overview (Tom Bozeman paper) |

| Scriver Blog |

| see also http://prairiemary.blogspot.com/2011/11/httpwww.html |

| Additional Citations |

Some typographical errors

have been found and corrected. If you suspect errors, please email vern@cres.org.

| [1976]

W o r s h i p 79 June 800 An Abraxan Essay Worship 1. WHAT DOES WORSHIP MEAN? WORTH, CONNECTION, ORDER. “Worship” is sometimes narrowly understood as bowing down to some supposed deity. The etymology of the word, however, leads us to a far more significant activity. The root of “worship” is worthship, considering things of worth. “Religion” (religare) means to bind up, to reconnect, to get it all together. Worship is thus the central activity of religion because through worship we reconnect with worth. Worship is a compelling vision of life in its fullness. Its scope, diversity, coherence and power engender the fundamental meanings, values and relations for our lives. Worship centers us. It gives us a perspective that orders the Void, the chaos of unconnected fragments of experience. Through worship we find our connections and take our place in society and the cosmos. Here beholding and becoming are the same. THE CREATION AND CELEBRATION OF HUMAN VALUES AND MEANINGS. It is fashionable nowadays to describe worship as “the celebration of life.” This too easily becomes a party or a vague sentiment. Worship is the celebration of life in its depths—intimate, intense, and ultimate. Through worship we discover, enliven, enrich, create, order, enhance, and empower what gives life worth. We experience awe, wonder, flow, fitness, appreciation, refreshment, and commitment. THE WHOLE. This does not mean there is an ontological Whole or Absolute Worth. It does not mean that all things actually fit together. On the other hand, worship is not illusory or simply “subjective.” It does mean that worship is the activity that fits things together, that reaches toward a whole as we create ourselves and our world. SPONTANEOUS WORSHIP. One can worship alone, “communing with nature,” in the ritual of a sport or other play, in work and in social action. Worship is not necessarily an orderly, regular calculated process, though it always creates order. Worship is more like falling in love, like being struck with the majesty of Mont Blanc, or like the surprise and gratitude we feel when someone touches us deeply in an unexpected way. For the creation and celebration of values, meanings and relations appears accidental perhaps as often as devised: if directed, then often outside ordinary awareness. The spirit of God, before creation, brooded on the waters before there were even any words. So our spirits hover in the Void, until we discover meanings emerging. Thus Schweitzer came upon “reverence for life,” Einstein formed the Relativity theories, and Mu Ch’i painted his “six Persimmons.” After considerable brooding, each integrated values into a larger whole in a moment of high awareness, of spontaneity and freedom. Such a consideration of worth occurs when the horizontal and the vertical—the mundane and the transcendent—suddenly intersect for us. There we gain awareness; we create a new or renewed order through which the entire universe plays. 2. PUBLIC WORSHIP DELIBERATE WORSHIP. Thus we rejoice when we unexpectedly find ourselves worshipping. But there is also place for the deliberate, labored consideration of values, whether they be themes Beethoven nurtured into the Fifth Symphony or the relation of First Amendment freedom of the press with Sixth Amendment guarantees of jury impartiality. Conscious and intended worship seeks to name our gods—to identify our values—even if they be such only for the never-ending moment. Hidden and unacknowledged gods can rule our behavior without our knowing it. Naming our gods and taking responsibility for assessing their worth enlarges our freedom. When we find we hold conflicting values, we may be alienated—unconnected—from ourselves and each other. Worship is the healing of such splits. IDOLATRY. Regular worship, a continuing reconsideration of values, as our lives and society change, prevents ossification and idolatry by guarding us from confounding the proximate with the transcendent. The discipline of deliberate worship thus is a source of expansion and freedom. Giving thanks even for the unknown, we can in high awareness choose the ways of growth, proportion, and flow. “WORK OF THE PEOPLE.” The church offers the discipline of deliberate worship. A community of faith, the church adds the dimension of human life to worship in nature. Private and public worship enhance each other. The presence of others who challenge and enrich our lives with competing and supporting agendas and priorities gives us additional eyes through which to see the universe—to reconnect us to ourselves, one another and the cosmos. Public worship then is not a presentation; it is involvement. It is not a lecture, concert or program. Liturgy means “the work of the people.” EXPERIENCE, NOT EXPLANATION. Liturgy is an immediate yet eternal experience which demands the participation of everyone in the religious community. It is not a simulation of some other experience, like theater. It is not merely an explanation of the way things are or ought to be. Liturgy transcends various styles or levels of interpretation since it is a prior unity of experience. For example, two persons taking part in mass may have different explanations of it and of the world. One may understand things quite literally; the other may give a mythical or metaphorical interpretation. The important fact is that they are both taking part in the same event, a sign of their human bondedness to one another and all life. Liturgy thus permits greater freedom than do rhetorical injunctions. While exegesis often divides, liturgy encourages “unity in diversity.” This does not mean intellectual precision is unimportant. Theological homework is required. A “worship arts” committee, more dance and drama, a new organ or a poetical sermon without transcendent reference will fail to meet the deepest human needs. Nevertheless openness to the experience of transcendence is more important than a precise analysis of what is or is not. PLAY. Worship, like sex is a supreme form of play. Play liberates us from the work mentality that seeks (at least functional) absolutes by which to judge our activities. In play, in worship, we need no reason outside life to give life meaning. Some attend church as an obligation, to justify or earn their existence. Such an attitude profanes life’s character as a gift, unearned and unearnable. In worship we celebrate with wonder and gratitude the meaning of that gift. The consequent responses we seek to make are not to earn life, but to revere it in centered faithfulness. 3. WORSHIP IN THIS AGE A VISION OF WHOLENESS. Our secular age gives us little access to a vision of wholeness. Our fragmentation masks from us the import of the human story. In our time it is difficult to find genuine open community. There are few tribes of people who trust one another enough to deal openly with the question of what is important in life. (New communities are appearing now, but often they are not open. Rigidly defined by narrow allegiances, they themselves participate in and perpetuate division in the world.) Our secular age has abandoned, demeaned or trivialized human rituals through which one once gained access to the whole. This situation also makes the development of new worship forms awkward and vexing. We have been parted from ourselves by rejecting ancient and humane customs and institutions. We have blasphemed the process which created new forms of Ordering. Simply because an institution—the presidency, the church, communion—has been abused, used hypocritically, deeply stained in many cases—is no reason to abandon it. The fact that love and friendship have been betrayed (which is very much the Passion story) does not require us to renounce these values (a discovery named Easter). Nor are past failures any excuse for refusing to fashion new rites and institutions. RITUAL. Nevertheless, we are beginning to appreciate ritual. Ritual is done by custom, rote or habit. Much of our lives depends on ritual: tying our shoes, brushing our teeth. If we had to lean how to drive a car each time we got behind the wheel, life would be intolerable. Some ritual is needed in much of what we do. Ritual frees us to use the vehicle to go somewhere. But ritual alone is a blank book. Liturgy (the work of the people) fills the book with meaning. A prayer that appears a superstitious ritual to an observer may be to the participant a profound act of spiritual awakening. AN ABRAXAN IRONY. If worship is the reconnection, the integration of experience, then it is possible only if there are real fragments needing unification. The very alienation of our age gives us the opportunity for empowering liturgy. Our corporate worship seeks to embrace and connect individual resources and priorities. So “evil” and “alienation” cannot be excluded as we move toward the whole. It is the tension between the actual and the ideal which not only wants resolution through worship but which inspires it in the first place. THE SIZE OF THE LITURGY. Because our lives are varied and few of us are at identical places in our cognitive and emotional development, public worship must be large enough to address different ages, classes, conditions, and concerns. The liturgy must embody all organs of the human adventure, with all its directions and contrasts. Such liturgy reorders our differences in the large view and makes them whole. Liturgy appealing only to the "traditionalists," or the iconoclasts, or the, successful or the visitors, is a liturgy without the dimension and integrity which stretches, restores and renews our lives. Only a very large liturgy can speak to all of us. If we are to grow religiously, we need worlds of vision beyond those we know now. If parts of the liturgy fail to speak to us at one point in our lives, it may mean there are worthy things yet to behold. Only a very large liturgy can speak to us for a lifetime. HOW THE EXPERIENCE IS FORMED. While spontaneity is possible and desirable, public worship enables rich and durable forms of worship to emerge, just as a symphony is developed. Many liturgical forms epitomize the history and possibilities of human interaction. Some of these forms are no longer suitable but many have been unnecessarily neglected and deserve renewal. The smells, vestments, motions, phrases, sounds and houses of worship themselves can convey and further the ordering of awareness, the design of fitness and fullness, the reconnections of genuine faith. The liturgy, with its psychological order and theological sequence, is the central means through which individual participants discover their parts in the human enterprise, and by which the church itself finds and expresses its corporate identity. LITURGY AND THE WORLD. But liturgy is more than an instrument of the individual and the church. The self and the world, spirit and politics, intersect in liturgy. Through liturgy we change the world by changing ourselves. Worship brings it all together. Through liturgy we involve ourselves in the larger society with greater vision and effect. In worship we freely touch the changing world with access to the experiences of the past and the present with the imagination and invention of a people honestly sharing their personal religious pilgrimages together in tribal celebration, in centering, in ordering. WORSHIP AND SEX. If worship involves the intimate, the intense and the ultimate, then worship is to the church as sex is to marriage. Like the sexuality of marriage, worship cannot be its only activity or its exclusive basis, or it has no real life in the world. Yet the worship of the church, again like sexuality in marriage, is the essential sacrament defining and enlivening other personal, social, economic and political sides of the institution's life. Further, like sexuality in prostitution, dead forms of worship are detached rather than intimate, shallow rather than intense, and trivial rather than ultimate. Moreover, a church without worship is like a platonic marriage, meeting special needs of a few but for most failing to command the interest, energy, imagination and commitment of a rich relationship. The obvious alternative to regular worship with a community of faith is to remain single (unchurched). 4. THE UNITARIAN UNIVERALIST EMBRACE THE WHOLE PERSON. Just as worship is an act of the entire community of faith, so it is an act of the whole person—intellect, esthetic sense, body, emotion. Literal truth is too confining: We would lose Beethoven, Rembrandt, Shakespeare and maybe even Emerson with a creedal test. Many important decisions—such as choosing one’s spouse—are not made simply by intellectual calculation. Pure emotional appeals are too transitory to reorder one's vision with clarity. The liturgy demands our presence as whole persons involved with one another, and thus reconnects us. This sometimes means singing or saying something we may not literally believe but which, from another perspective, informs our experience. Many of us left Christian churches that required literal acceptance of creedal statements, and offered few alternative modes of expression. What is important is not so much the words but rather the experiencing of legitimate religious moods and modes, no one of which can be taken as final and completely comprehensive. OUR GENIUS. We find it easy to enjoy different kinds of people and viewpoints. We can rejoice in many languages. We can love Dante even if we cannot accept his cosmology; we can sing the Beethoven Credo even if we cannot subscribe to it; we can feel and revere the 1905 Symphony of Shostakovitch though we abhor communism; we can participate in a Hindu chant without compromising our own mythologies; we can enjoy Christian communion without patching it up to fit our own prejudices; we can teach "Silent Night" to our children though we disbelieve the Virgin Birth; we can be moved by Hamlet while we deny the existence of ghosts. We can sing, we can dance, we can rejoice without censoring any honest hallelujah or plea for help. Our genius is being able to see God, the Void or Whatever, working in every person and place. 5. THE UNITARIAN UNIVERSALIST OPPORTUNITY UU CONTEXT. Our churches, especially where liturgy is not automatic or routine, have an unparalleled opportunity today for the renewal of liturgy. Where clear-thinking people celebrate their companionship with one another and with human struggles through out the ages, separations can be healed through the revival of the art of worship. However, just as it is difficult for someone who has never heard baroque music to understand the musical language of Bach, so we must overcome the prejudice against liturgical forms to develop and communicate with a rich religious language. Such a language appeals to the entire person. Without it Unitarian Universalism will continue to be for many a revolving door into the secular world. Without it our children will find our intellectual emphasis inadequate to sustain their commitment to our movement, as they will also find the cute "smelling the flower is worship" too weak to inform their decisions with wisdom. With a rich liturgical tradition we can build temples of meaning and societies of justice. DISCIPLINE. To develop an empowering liturgy, the professional UU leadership must turn from the charismatic model. The churches must turn from narcissism. No longer may we pride ourselves as mavericks. We must become virtuosi in the art of worship. Instead of inventing the wheel each week in each church in our individual ways, we must develop disciplines for sharing the technical as well as "spiritual" aspect of worship as we use it and live it in our churches and lives. While each congregation must retain control over its own worship, such disciplined sharings—tested through wide rather than idiosyncratic usage—offers a hope for moving beyond pulpit exchanges and shuttling programs towards a body of powerful common liturgy adaptable to specific situations. Such disciplines would refine, enrich and enlarge our practices into a genuine living and growing liturgical tradition. 6. OUR WORK This is the work of the Congregation of Abraxas: liturgical renewal. We believe the human enterprise and the health of our churches requires above all else the capacity and vehicles for genuine private and public worship. We want to renew liturgy in our lives so it will renew us and our society. We hope the suggestions of this essay are part of an open Renewal process. ABRAXAS—An order of Unitarian Universalist ministers and lay people who see worship as the center of our liberal religious life and work, and who have joined together to develop liturgical materials through a collegial process. Drawing on Eastern and western religious themes, the group is concerned with the forms and content of both public worship and private devotional discipline. Friends receive mailings from the group. General Members participate in collegial writing and decision making. Ordered Members take upon themselves a special discipline of work and sharing. Membership in all levels is for a year at a time. Samples of published materials and further information about the Congregation and its retreats can be obtained by writing the Executive Secretary at P.O. Box 4165, Overland Park, KS 66204.[No longer available -- write P.O. Box 45414, Kansas City, MO 64171.] This essay, originally a pamphlet (1976), appears on pages 22-26 in the 207-page 1980/81 volume, The Congregation of Abraxas Worship Reader and Supplement: Essays in Worship Theory from Von Ogden Vogt (1921) to the UUA Commission on Common Worship (1980) -- copies of which should be at the theological schools. This essay was drafted by Vern the Void and perfected by comments from Duke the Dumb, Fred the Full, Stephan the Spare, and Harry the Holy, all in agreement with every word. |

|

Abraxas was a big part of my life. The five of us

(Harry the Holy, Duke the Dumb, Fred the Full, Stephan the Spare -- and

I was Vern the Void), all Unitarian Universalist ministers who started

the group in 1975, studied the Rule of Benedict and decided to form ourselves

as a "liturgical and missionary order" for our fellow UUs (our mission

field), who, we felt, too often practiced a shallow and impotent form of

Sunday assembly. We took vows paralleling poverty, chastity, and obedience:

http://www.cres.org/pubs/abraxasG.htm

.

Originally our monastic enterprise was for the five of us, but as people found out about us, they wanted to join, so we developed postulancy and ordination processes as folks (mainly lay) wanted to come to our retreats, some as long as eight days, sometimes as many as twenty lay people, which we held around the continent, from New York to Berkeley to Toronto. Most clergy seemed uninterested in anything that would upset their routine worship (usually sermon-focused rather than sacramental practice). The hunger for real worship was apparent whenever Abraxas offered worship opportunities. For example, a rabidly humanist fellowship took a chance with an Abraxas Eucharist. Careful preparation of the congregation to lower the literalists' fears led to remarkably full participation in the sacred rite, even by vociferous atheists. The relative disinterest of the majority of UU professionals to engage deeply in examining worship practices when it became clear that the laity, usually unknowingly, hungered for something more than an interesting and inspiring lecture, has been crushingly disappointing to me. My own good fortune in serving a congregation that welcomed all sorts of explorations and experiments in worship led to remarkable energy and reward. Whether it was Christian Midnight Mass (I was warned no one would come, but by the second Christmas the church was packed), Buddhist Wesak observances, Sufi dances, Jewish, Hindu, American Indian, and rituals of other faiths respectfully, all informed by Abraxas sensibility -- and of course Abraxas-influenced liturgies. My ministry concluded with the worship committee designing its own liturgy using the Abraxas four-part theory of liturgical design. But denominationally, our success has been mainly in modeling for our colleagues the wearing of stoles or other vestments (following our presentation of a stole to then-UUA president Gene Pickett who wore it at General Assembly), though we claim some contributions through Fred Gillis (one of the O.F.= Original Five, also known as Old Farts) who served on the Commission on Common Worship, and Mark Belletini who chaired the Hymnbook Resources Commission, and later Wayne Arnason. "Wayne the Wide" (and Kathleen Rolenz) whose book Worship that Works: Theory and Practice for Unitarian Universalists shows a continuing interest in thinking about worship practices. Occasionally students will be intrigued about our work and some claim to be influenced, but I see no signs that the basic study we did, and explorations we charted, have provided any significant improvement to UU worship. Sometimes I hear of Abraxas materials being used or adapted in some way, and I wonder if this is being done in a charismatic (leader-centered) or virtuoso (congregation-centered) manner, so I am relieved when I hear the focus is on the gathering rather than on the presider, on a world-wide heritage shared into the present hour rather than on the presumed wisdom of a particular person. A liturgical format (liturgy="the work of the people") makes the widest scope possible, and the use of the "cadenza" encourages spontaneity supported by structure. I have been greatly enriched in many ways by Abraxas. Since our emphasis was on the virtuoso, the skilled and trained one, not the charismatic, excessively personal style, we considered it of great importance to train folks how to lead liturgy as well as how to draft liturgical forms (our official publications were always "trial"). It may be as difficult to learn to lead worship from a book as it is to learn to play the piano from a book; experience, examples, a teacher may be a great benefit in entering a sacred tradition. Our commitment to publish only what was meaningful to all five of us, with vastly different theological perspectives (Christian and Buddhist to Humanist and atheist), led to transcendent discussions and worship, a great deal of learning and fun (our inside jokes still cheer me), as well as enduring affection.

A NEW RANT -- 2017 April 24 Ever since the 1968 Cleveland

GA, the UUA has pushed a demographic agenda and often neglected a religious

mission. So much wasted energy! So little to show for it! People of color

will be attracted when UU churches offer a comprehensive spiritual experience

instead of the diversion of the moment or in-group.

1st Principle:

The inherent worth and dignity of every person;

Six Sources

John

McWhorter (NYTimes 2024 March 28) writes of a concern about anti-racism

efforts in many universities which, in many ways, parallels the problem

in UU churches: On Broadway, ‘centering’ antiracism is delightful. Why is it so dreary in universities?

|

|

from http://prairiemary.blogspot.com/2011/11/httpwww.html Wednesday, November 30, 2011

http://www.uua.org/worship/theory/abraxanessay/ At this url is an essay written by a group of ministers and lay people who belonged to the Unitarian Universalist Association. Now it is part of the UUA website called “Worship Web,” which is particularly needed in this denomination because many of the small congregations are lay-lead and don’t have a trunk full of things to read or any real certainly about how to go about organizing worship. They may have come from places where it just wasn’t done by laypeople. Sometimes even as a professional and experienced minister, it really helps to be able to find something specific. One of the main leaders of Abraxas was the Rev.

Vern Barnet, now working at http://www.cres.org/pubs/abraxas.htm (Community

Resource for Exploring Spirituality) though the formal organization may

have tuckered out. It appears that even the indefatigable Vern is now “emeritus”

and writing. Here's Vern: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eTCBKUp42kM

Abraxans loved paraphernalia, vestments, smells and bells, secret names. They were very traditional, but would mix traditions within their prescribed ceremonies by using a reading from Hinduism, or a little ritual from an obscure corner of Christianity. It’s a style that came from the Sixties/Seventies comparative religion studies. Things can get a little confused with such an approach. I remember a time at the UUA general assembly, when some Buddhist priests had been invited to perform their liturgy. The audience, wishing to do the right thing, imitated the priests by standing and sitting or whatever, (paper fans were involved so the people used their programs) as they would have in a Catholic mass. This disconcerted the priests, who came from a tradition where the important people do the stuff while the congregants merely observe. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nhNtBWFbW0 This ten minute YouTube vid is a little service to view privately. The UU Chalice is there, with a double-circle for the Unitarian-Universalist overlap, the music is gospel and a well-known contemporary song. The sentiments are inclusive, so that the martyrs include Harvey Milk and many others, plus ringing spaces to indicate that there are more and more of them than we know. (I expect there was a gong bowl rather than a bell.) Many religions are mentioned. It’s hard to see how anyone could be offended. But to me, that’s sort of what’s wrong. It’s so generalized that it is -- forgive me RevWik (Erik Walker Wikstrom) -- bland. It’s over-familiar, very Sixties and Seventies. But then, that’s probably who’s there in that congregation, what they know, what they have used as an operating principle for the last decades, and what helps them keep their bearings. If a person came along and started challenging the idea that love conquers all (which is not very hard to do) they’d be considered a trouble-maker and if there were too much trouble, love would pitch trouble out the door -- and that’s what they SHOULD do. As it says in Robert’s Rules of Order, a person who is not in sympathy with the purpose of the meeting may be excluded. The Roman Catholic Eucharistic Mass is from the same liturgical patterns as Abraxas except for sticking to prescribed historical words that have been used for thousands of years. In the Sixties and Seventies they too “loosened up” by including guitar players with the organist, unscrewing the pews so they could be put in a circle, and using an English translation of the Latin mass. The result was uproar and residual resentment -- now reversal. Just a few days ago another new English mass was introduced and there was less emotion, but it was NOT comfortable for people who were used to the memorized words rolling out in a litany. http://www.danielharper.org/resource13.htm#plan Here’s an interesting blog about what is called “Circle Worship” which kind of riffs off of Starhawk. The actual order of service is familiar, not far from what people kiddingly call a “hymn sandwich.” Daniel Harper is a Minister of Religious Education, which has a special concern for children and that shows up in this service. Again that same “nice” sort of “arty” context with a lot of earnest idealism. Familiar, pleasant. Quite like a concert attended with friends. Such a context can be an oasis for some people but it does not exactly change lives. There’s not likely to be a spiritual breakthrough into other worlds or an epiphany of new understanding. Halfway between the Masonic Lodge and Bahai, but always in a familiar pattern laid down long ago, content wobbles between therapeutic counseling and post-WWII social action. The stream bed is wide in some ways, but the people attracted by tolerance and plurality are not likely to be cutting edge. On the other hand an amazing life-changing experience every Sunday would only wear everyone out. This is the problem of the whole United States “experiment,” as some call it: that it is meant to include everyone but doesn’t always (it DOES sometimes) or dare to power change even when the status quo is cooking the frog. Abraxas was an admirable experiment in re-invigorating the medieval models by reaching out for world-wide words and practices, something like the New England Transcendentalists realizing what Buddhism and Hinduism had to offer and pulling it into their Christian thinking. But they are never going to kill roosters in church because Santeria might do that. They are never going to use Sun Lodge ordeals in which chest muscles are torn. And they are never going to throw up their hands and speak in tongues and fall on the floor. Worship styles are almost always class-based and so are denominations. Even the more radical experiments like those at UU Leadership School stay within UU culture, elastic as it can sometimes be. I’m just the kind of bear who wants to go over the hill to see what I can see. Which is why I left the meeting. Posted by Mary Strachan Scriver at 8:43 AM

A Response from Vern Barnet-- 1. Shallow syncretism is to be

eschewed, and fiddling with the Mass must be done with care (some complain

Vatican II failed to fiddle with the Tridentine form with skill). But Abraxas

cannot be understood simply as a cafeteria liturgy. (Shall we accuse TS Eliot of syncretism because he integrates insights from Hinduism and Buddhism

in his "Four Quartets," perhaps the most profound Christian poem of the

20th Century?) A scholar- and experienced-based understanding of

various faiths may lead to a respectful informing of a liturgical

effort which is anything but mere syncretism, though it must be noted

that Christianity arises from Hebrew sources, Hellenistic practices

themselves syncretistic, and pagan themes, and UUism may be the

ultimate mess of various shallowly-understood spiritual and secular

sources. (Some forms of Buddhism are not alone in expecting worshippers

simply to observe -- forms of the Tridentine

Mass and Christian Orthodox services have similar expectations for the

worshippers; and in other faiths, types and degrees of

participation vary greatly.) (BTW,

I have received over a dozen honors from Jewish, Christian, Buddhist,

Hindu, Sikh, Muslim, and interfaith organizations, and many other

awards, and was hired by The Kansas City Star to write a weekly column

on various faiths; and I have taught world religions at the college and

seminary level; so I have at least some acquaintance with various

traditions which have sought to recognize my fairness in writing about

them, 1994-2012. I was also one of four editors of a multi-faith handbook for health-care providers, published internationally. I have also taught worship for seminary students.) 2. A distinctive, unprecedented

four-part liturgical format was developed, informed, surely, by past Christian

patterns and by Von Ogdan Vogt's five-part worship plan. That 4-part sequence

in turn arose from study of anthropological, sociological, psychological, pedagogical,

literary, and theological examination. It was tried and found successful.

Recognizing this contribution to worship theory and practice is an important

part of evaluating what Abraxas did. updated 2024 #retreat_story undated newspaper clipping Abraxas retreats seek meaning of 'the ordered life' By Wayne Arnason Matins, Eucharist. Vespers, Complinei These are words not otten heard in descriptions of Unitarian Universalist spiritual practices. Yet the services of worship called by these names form the benchmarks of each day of the retreats held by the Congregation of Abraxras. The Congregation of Abraxas is a group of women and men. laity and clergy. within Unitarian Universalism who are seeking to understand the meaning of "ordered lite" in a liberal religious context. Drawn by the power of worship as a personal and a collective spiritual discipline. the members of the Congregation of Abraxas gather for at least three major retreats each year. Many UUs have shared in one or more of the services at a General Assembly. However. these services were not created for that type of parish use. They are intended for repeated use in a monastic setting, and their meaning and power changes within that context. What does a "monastic setting" and an “ordered life" mean for Unitarian Universalists? A look at the retreat at the House of the Redeemer. a retreat house in New York City. Oct. 22-26 offers some answers. The eleven in retreat include "born-and-bred" UUs as well as the 'born-again" variety who grew up in Methodist, Baptist. Episcopal or Catholic churches. Each retreat day follows a regular pattern which repeats itself in the rnoming. afternoon, and evening. The pattern includes worship. a meal. personal free time. spiritual exercises, program or business discussions, recreation, and a time period whidh might include work, alone time, or social time depending on the hour of the day. The day begins with the Matins, or moming service. written to celebrate the [dawn with a focus on the natural world.] Before the noon meal, the Abraxan Eucharist, with

its themes of community

As evening comes, the vespers service invoking re?ections on our personal and collective history is said. The last service of the day, Compline, stands outside the three-part retreat pattern. for it begins a different part of the day. Compline's theme is psyche and inner life, and following the service the participants in the retreat keep silence until the first words of Matins are spoken in the morning. Meals are usually taken with some form of table discipline, which might be anything from directed conversation to refectory reading to silence. Not all of an Abraxan retreat is involved with discipline, however. People who have come to know the Abraxan style have grown accustomed to a paradoxical sense of humor which accompanies this serious interest in spiritual life. lt is usual for one block of time during the retreat to be devoted to a group excursion. which this year involved a walk through Central Park ablaze with tall foliage and an aftemoon at the Museum of Natural History. Whenever possible, the retreat schedule on a Sunday involves sharing a service with a local UU congregation. The highlight of the fall retreat this year was the ordering ceremony at which four new members of the order were welcomed. ln the year past these four "postulants“ had completed a process of work, study, and personal discipline leading up to joining the order. The vows of the Congregation of Abraxas have drawn some inspiration from the Rule of St. Benedict in spirit. but not in letter. Rather than chastity, poverty, and obedience, ordncd members of Abraxas vow equity, utility. and collegiality with other members of the order and in their attitudes towards the world. ln the past two years the order has grown from seven to thirteen ordered members and several postulants still moving through the process leading to ordering. The next retreat will be in February in the Chicago area. Announcements will be mailed to all who are on the Friends or the General Member mailing list. or further information may be obtained from the Scribe of the Order at P.O. Box 4165, Overland Park, KS 66204. PHOTO Vespers --

|

|

Religious publishing houses, congregtions, and non-profits are welcome to excerpt and reprint Abraxan material without charge from this site and from our print publications by acknowledging the source. Citation may be made by adapting and abbreviating the following: [Name of specific publication], Congregation of Abraxas, a Unitarian Universalist Liturgical and Missionary Order (fl. 1975-1985), city of publication, copyright date/date of publication, page(s) or url]. Used with permission. NOTE that all Abaxan services were officially published as trials, so an excerpt from the Matins should be cited as "Trial Matins." This is an important point because Abraxans insisted on a process of continuing revision as essential to liturgical integrity -- publication otherwise misrepresents the intent and commitment by the Abraxans. Example of unshortened citation: "Trial Matins According to the Usage of the Congregation of Abraxas," a Unitarian Universalist Liturgical and Missionary Order (fl. 1975-1985), New York, revised 1979, page 2. Used with permission. A copy of the work in which the cited material appears should be filed with Abraxas CustodianFor questions or to confirm authenticity of material under consideration, address Vern Barnet, vern@cres.org . Thank you for your courtesy.

|

|

http://www.uua.org/worship/theory/abraxanessay/ At this url is an essay written by a group of ministers and lay people who belonged to the Unitarian Universalist Association. Now it is part of the UUA website called “Worship Web,” which is particularly needed in this denomination because many of the small congregations are lay-lead and don’t have a trunk full of things to read or any real certainly about how to go about organizing worship. They may have come from places where it just wasn’t done by laypeople. Sometimes even as a professional and experienced minister, it really helps to be able to find something specific. One of the main leaders of Abraxas was the Rev. Vern Barnet, now working at http://www.cres.org/pubs/abraxas.htm (Community Resource for Exploring Spirituality) though the formal organization may have tuckered out. It appears that even the indefatigable Vern is now “emeritus” and writing. Here's Vern: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eTCBKUp42kM I admired this organization and liked Vern, but

in 1978 I didn’t quite know how to approach this group. Abraxas, named

for an early god-idea, thought of itself as a monastic order in a joking

way. They were very earnest and yet jocular, which I know doesn’t mean

they weren’t serious, but it seemed like a cover for what I finally decided

was -- on the part of some members -- simply arrogance, a wish to know

more and be better and keep secrets. They declared themselves “spiritual”

but seemed to define that as “interfaith” among the major religious institutions,

including those that were Humanist. Vern still writes his religion column

for the Kansas City Star. Here’s the most recent column:

Abraxans loved paraphernalia, vestments, smells and bells, secret names. They were very traditional, but would mix traditions within their prescribed ceremonies by using a reading from Hinduism, or a little ritual from an obscure corner of Christianity. It’s a style that came from the Sixties/Seventies comparative religion studies. Things can get a little confused with such an approach. I remember a time at the UUA general assembly, when some Buddhist priests had been invited to perform their liturgy. The audience, wishing to do the right thing, imitated the priests by standing and sitting or whatever, (paper fans were involved so the people used their programs) as they would have in a Catholic mass. This disconcerted the priests, who came from a tradition where the important people do the stuff while the congregants merely observe.

https://uucb.org/groups-at-uucb/ Abraxas by Grace Ulp Abraxas, called the “Congregation of Abraxas” by the UUA, was a group of ministers and lay people interested in the form, art, and experience of worship. In size, small (never more than 40 financial supporters); in clout, less than they hoped. They gathered at a time when the UUA was growing its membership through Fellowships, mostly lay-led, with in some cases a lack of experience in providing worship services for their members. The famous “hymn sandwich” was a problem for seekers of worship: fill out an hour with a 50 minute lecture on anything between the atom bomb and the philosophy of God Is Dead, plus a hymn before and after. The group started out publishing a “Worship Reader”: essays in worship theory from Von Ogden Vogt to the UUA Commission on Common Worship. They held discussions at the UUA General Assemblies, and provided retreats for those interested after the Assembly closed. A group on the west coast (Abraxas West) published “Rite of Religion”: a booklet about the experience of worship, and “Book of Hours,” material for the worship services at retreats. They met frequently to hold worship services in the Starr King Worship yurt or in the UUCB Fireside Room. There also were weekend retreats—one at Zen Center’s Green Gulch Farm, and another in working meditation under the leadership of Blanche and Lou Hartman, Zen priests. Occasionally a worship service is still held, courtesy of one of our “Abraxans.”

https://www.uua.org/re/tapestry/adults/practice/workshop3/find-out-more The Congregation of Abraxas Worship Reader—includes several writings by Unitarian Universalist ministers.

http://www.wizduum.net/forum/congregation-abraxas Just wanted to let people know that the website for the Congregation of Abraxas is back online. Yay! Very Happy http://www.congregationofabraxas.org/ For those of you who are unfamiliar with them, the Congregation of Abraxas was a UU semi-monastic order that was formed in the 1970's during the height of the dominance of secular humanism on UU. A few people, dissatisfied with the lack of worship opportunities, got together to create uniquely UU liturgies and other aspects of worship. The UU hymnal that we use right now came out of their work. So if for no other reason we owe them a debt of gratitude.

https://caelesti.livejournal.com/40557.html

I have a book called "Earth Prayers From Around

the World, 366 Prayers, Poems & Invocations for Honoring the Earth"<input

... ></input><input ... > It contains some prayers that I really

like from a group called the Congregation of Abraxas. I was curious who

they were so I Googled them.

On a side note, I also wondered about the name "Abraxas"

It sounded to me to be vaguely Greek and ceremonial magicky- I was kind

of right it goes back to Gnosticism- the history of it is rather complex!

https://friendsofsilence.net/quote/author/congregation-abraxas Congregation of Abraxas

Eternal spirit of Justice and Love,

http://celestiallands.org/wayside/?p=790 There is a history of this… sortof. In the 1940’s and 50’s, a group of Universalist Ministers formed a group that was patterned on a “fraters” style religious order, known as the Humiliati. They focused on theological depth and on revitalizing the Universalist Church of America. There also was another group, known as the Congregation of Abraxas, which formed in 1975 as a group of both clergy and lay UU’s focused on revitalizing worship within our tradition. I have had the honor and privilege to have met with and spoken with some of the last members of each of these groups about their experiences, for which I am deeply grateful.

https://parzifal.wordpress.com/2006/11/11/congregation-of-abraxas/ In the 70/80’s I was a member of the Congregation of Abraxas–many worship items were produced in print form and many workshops were presented. I have gathered a very few ideas from the Worship Reader and they are presented here for your exploration. This was one of the few Liturgical Revivals in the UU church; another was the work of the Humiliati (primarily a Universalist liturgical movement). Below is a collection of CoAbraxas ideas.

The texts below originally appeared in the Congregation of Abraxas Worship Reader, pp. 53-76. May be printed for personal use only—authors retain their respective copyrights. etc

http://www.worldcat.org/identities/lccn-n86-78/ http://www.softconference.com/storefront/PDF/250624.pdf https://www.uuma.org/blogpost/569858/168584/In-Memory-of----

http://uufeaston.org/download/Sermons/Sermons

https://uurainbowhistory.net/personal-memories-of-lgbtq-groundbreakers-in-the-uua/ https://www.boyinthebands.com/archives/do-unitarians-have-a-liturgy/ https://theisticsatanism.wikia.org/wiki/Abraxas https://cse.google.com/cse?q=

https://www.amazon.com/Rite-Religion-Mark-Belletini/dp/B00641RUDY http://pagantheologies.pbworks.com/w/page/112082326/Worship https://uudb.org/articles/vonogdenvogt.html https://cdn.ymaws.com/www.uuma.org/resource/collection/

|