| Are

the world’s religions separate pieces of history and spirituality, or do

they, viewed together, form a pattern?

Dear Reader:

SINCE THIS ESSAY

APPEARED in 2000, “The Gifts of Pluralism” conference, Kansas City’s first

interfaith conference, was held with 250 people from 15 faith groups —

A to Z, American Indian to Zoroastrian. From that conference a number of

clarifications and new insights have emerged. In addition, many comments,

suggestions, and criticisms of this essay have been offered, for all of

which I am grateful. These are collected and awaiting incorporation in

a revised version of this essay, which I expect to make early in 2003.

You, dear reader, especially after 9/11, are also invited to contribute

your questions, responses, and criticisms for that revision. Please send

them to me: vern@cres.org or Box 45414, KCMO 64171. Thank you.

August, 2002

NOTE.— Since this

draft was issued, the crises in all three arenas — environmental, personal,

and social — have deepened. To update just the domain of our business system:

Microsoft’s practices have been found illegal, and the scandals of accounting

and executive compensation are now no longer secret. These and other matters

have not yet been incorporated into the present text which awaits revision. |

|

1.

Three Crises; Three Responses

THE CHIEF AND DEADLY DEFECT of our secularist

culture is fragmentation; that is, there is no vision of how all things

involve each other and of what things are most important, of what really

counts.

This means it is difficult to decide what

is worth living or dying for.

The secularistic

contrasts with the sacred, the holy (related to holistic, the whole), that

on which our lives depend.

This brokenness

shows itself in three domains:

— the degraded

environment, to which the ancient theological term “pollution” has now

been applied;

— the loss of

personal identity, evidenced by numbing codependent relationships and addictions;

— the deterioration

of social order, one example of which is the portrayal of violence as “entertainment.”

It is difficult for

us to see our situation clearly because we are enmeshed within it. But

the world’s religious traditions can provide us with bridges from which

we can view the currents of change.

INSTEAD of using such bridges to make sense

of,

or to envision reform of the secularism of today, two movements have themselves

become dangerous vortices.

l Fundamentalism

reacts, a whirlpool of waste. It insists it has the answers to our problems

in the exact words of the old texts of the One True Religion.

l On the other

hand, the New Age scavenges. New Age doctrine proclaims that all religions

are basically the same, but its practice sometimes focuses on crystals,

astrology, past lives, or ecstatic episodes, more than on fulfilling the

claims of faith to do good for one’s brothers and sisters.

l We propose

a third response, a response that grows out of an examination of what is

sacred in each faith. We believe that the world’s religions provide us

with the resources to address the three domains, broken in us as individuals,

as communities, and as members of a fragile biosphere. |

The urgent project

for our age is this: to discover how the answers from the world's religions

to the question “What is sacred?” mutually interpenetrate and inform each

other. Unless we do this, the sacred will remain fragmented and our culture

will teeter more precariously above a secularist hell.

|

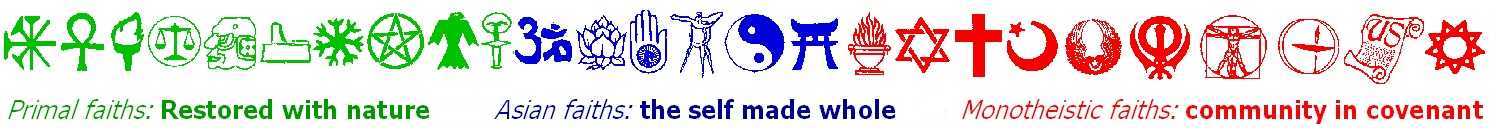

2. The Paths

of Healing

THE SACRED, that on which our lives depend,

is generally located in different realms by the three families of faith.

1. With significant variations,

the Primal religions, including ancient practices of the Mesopotamians,

Egyptians, Greeks, and Romans, the Maya and the Inca, and the almost extinct

traditions of the American Indians and tribal Africans, and the Wiccan

tradition now being recovered, generally find the sacred in the world of

nature.

2. The Asian

religions, such as the faiths arising in China, Confucianism and Taoism,

and the faiths beginning in India called Hinduism and Buddhism, generally

locate the sacred in inner awareness.

3. The Monotheistic

religions, including Judaism, Christianity, and Islam (and one might add

Sikhism, Unitarian Universalism, Bahá’í, Marxism, and what

scholars call “American Civil Religion”), find the sacred disclosed in

the history of covenanted community.

This is not to

say that the sacred is nature, or is inner awareness, or is the history

of covenanted community. Rather, in general, these families locate the

sacred in these realms. Of course there are exceptions and variations and

subtleties. Shinto is an Asian religion that in our scheme belongs primarily

with the Primal faiths. Zoroastrianism is a special case since it greatly

influenced the Monotheistic faiths while its origins are not Abrahamic.

But the scheme we outline, despite its limitations, can be useful in three

ways:

— to provide

an overview of religious consciousness throughout history and the world,

— to guide a

“research program” for deeper understanding of the faiths, and

— most importantly,

to show us paths to the healing of the afflictions of our age.

For example,

we cannot be rescued from ecological doom only by technical solutions;

a spiritual reorientation is required by which we understand our kinship

and interdependence with trees, rocks, the air and water, not to be used

so much as to be honored.

The insights

of each of the three families are easily perverted (see

chart). The Primal faiths often degenerate into superstition; the Asian

faiths into narcissism; the Monotheistic faiths into self-righteousness

and militancy. Today dialogue amongst the faiths can lead to mutual purification.

However, even

the purest, fullest, human understanding of any separate revelation is

no longer sufficient for us as a society because we cannot understand fully

any one tradition without being acquainted with others. The additional,

urgent project for our age is this: to discover how the several answers

to the question “What is sacred?” mutually interpenetrate and inform each

other. Unless we do this, the sacred will remain fragmented and our culture

will teeter more precariously above a secularist hell. |

Religion

arises from the Holy; religion is the discovery of how

to

live in the world. The Holy leads to awe, then gratitude, then to service

—the Holy in action. |

3. The Holy

THE HOLY is that on which our lives depend,

ultimate concern, or ultimate commitment, the cornerstone of all values.

The English word is related to “health,” “wholesome,” and “holistic.” We

sometimes sense the holy in “peak experiences.” Such experiences shape

or direct or give meaning to all of life, and are rivers of the spirit.

These experiences make us vividly aware of what is valuable, connect us

to our deepest selves — and beyond ourselves, to the Infinite, and give

us perspective. The Holy, the sacred, is what is worth living for, and

dying for.

Religion

arises from the Holy; religion is the discovery of how to live in the world:

“What is so important that my life depends upon it, and what must I do

to honor and share it?”

In philosophy

the sacred is called Reality; to use information science language, it is

the Structure of All Data. The sacred is supreme worth, fundamental significance,

ultimate value, utmost concern.

The sacred is

contrasted with the profane, the fragmented, the partial, the instrumental,

the means. Our culture is secularist because it so often avoids beholding

the sacred, the whole, and instead seems preoccupied with fragments.

Unless we are

frequently recalled to the Holy, we lose the perspective, wholesome energy,

and connection that makes life meaningful. Our secularist society distracts

us from the Holy, rather than supporting our immersion in it. The trance

of our culture places the Holy at the edge of our awareness, instead of

at the radiating, nourishing center.

Immersion in

the Holy leads to reverence, awe, clarity, attention — “beholding.” When

I behold, I see without agenda, for having an agenda shapes, deforms what

I see, inhibiting clarity. The addictions, compulsions, repulsions, inhibitions,

prejudices, paranoias, hang-ups, consumptions, and co-dependencies that

characterize our age make beholding difficult. We cannot clearly see who

we are, what our situation is, or what we must do. But with the freedom

to see clearly things as they are — especially to see ambiguity instead

of falsely defined situations — we live a fit, genuine life.

In beholding

the Holy, we apprehend ultimate worth. The Anglo-Saxon term from which

our word worship derives means “shaping” or “scooping” or “considering

things of worth.”

Such beholding

often leads to gratitude, which in turn often leads to a desire to share

and be of service as a way of rendering thanks. This is why the sacred

opens, organizes, and prioritizes our living, and gives us a power and

authenticity that links us to the energy of the universe itself.

Spirituality

is a way of living out our worship experience so that our lives have transcendent

meaning, coherence, order, and relationships informed by a sense of the

Sacred. Spirituality is breathing with a sense of what counts.

To eat or love

or travel or listen or work or play or walk through a field or email a

friend or attend a concert or a game or heal or comfort a companion or

even breathe with sacred intent throws one into awareness of infinite connections

and ultimate dependencies. The world is vivid, we belong in it, and we

want to help. |

| Our

age is secularistic because it has no unifying sense of the Holy.

The profane, the partial,

separates the method from the result, the means severed from the end. The

slogan, “The end justifies the means,” is rejected by those who, like Gandhi

and King, understand that there can be no sacred distinction between the

two.

One does not build a nonviolent

society through violence. |

4.

Three Profanities of Our Secularist Age

THE WORD PROFANE means “outside the temple,”

but even the temple has often become profane, secularistic, in the sense

of being disconnected to the rest of our lives. “Profane” and “secularistic”

point to the fragmentation of our world into various disciplines (in the

universities), special interests (in politics), and social divisions (by

class, race, age, “sexual orientation” and such).

The profane is

the opposite of the Holy, that which is whole, the network on which all

depends. Our age is secularistic because it has no unifying sense of the

Holy.

The profane,

the partial, separates the method from the result, the means severed from

the end. The slogan, “The end justifies the means,” is rejected by those

who, like Gandhi and King, understand that there can be no sacred distinction

between the two. One does not build a nonviolent society through violence.

As Abraham Lincoln knew, when violence is necessary, a terrible price must

be paid. The effects of slavery brought in the New World in the 15th Century

still have not been healed. We profane • nature, • self, and • others.

The Ecology.

— The destruction of rain forests is one example of the environmental exploitation

arising from the secularism that fragments and profanes us. If we deeply

sensed how holy these forests are, and that our survival depends on their

well-being, we would not cut them down any more than we would poke out

our own eyes.

Our environmental

danger is sometimes summarized by the word “pollution,” actually an old

religious term denoting ritual desecration and moral corruption. Overpopulation,

toxic wastes from the auto, and the loss of diversity of species are signs

of this pollution. “Pollution” cannot be corrected by mere technology because

it is ultimately a spiritual problem.

The Person.

— Within the individual, the profane divides us from ourselves and leads

to three kinds of failure. The first is addiction. It may be to substances

like alcohol and tobacco, or to compulsive behaviors like gambling, sexaholism,

and workaholism, or to the kind of consumerism which distracts us from

recognizing the sacred in the ordinary. The second is dependency which

keeps us from taking responsibility for ourselves by co-dependent relationships,

handling others’ feelings, and destructive criticism of others. The third

is prejudice — acted out in oppressions like sexism, classism, heterosexism,

adultism, age-ism, limiting our spirits and distancing us from others.

Society. — We are addicted to violence. Its portrayal often ignores its

actual effect on victims and their families, further violating reality.

Games like Mortal Kombat engender competition to see who can lop off the

most heads in stylized “fun.” With advances in virtual reality computing,

it will be possible to actually feel what it is like to cut open someone’s

chest and pull out the beating heart, with your victim’s warm blood spurting

in your face. There will be no immediate consequences since it is just

a simulation. But such electronic rehearsals, profaning the spirit, will

result in actual performances. The celebrity status and huge financial

rewards that we give writers, actors, and companies that model violence

show we have not been effective in shaming them.

Our entertainment

paradigms are win/lose battles instead of creative, respectful, loyal conflict

out of which solutions which benefit all people emerge.

Is any

aspect of our society more profane than sexuality? Our culture has often

disconnected it from spirituality and turned it into a commodity. The frequency

of rape suggests that power, rather than mutuality, is society’s theme.

Most faiths agree that sex is one possible way to express or explore transcendent

love. But there is disagreement whether law and religious rules too often

treat sex as a merely physical activity. For example, should the love of

partners be expressed in marriage if they are of the same gender? Does

a negative answer arise from a physical preoccupation?

If there is an

area more profane than sexuality, it may be the exploitation which creates

the growing disparity between the very rich and the very poor. This is

happening because our disengaged citizenry too often focuses on private

matters instead of our common weal. Repenting our selfishness and greed

may be more important than tax-cuts.

|

|

5. The Holy in

the Environment

MANY PRIMAL RELIGIONS behold the sacred

in the world of nature. Unlike creationists who fear the notion that we

might be related to monkeys, the American Indian celebrates one’s bear,

fox, or frog lineage, an ancestry which gives one intimacy with nature.

This is why totem poles, family trees, portray one’s forebears in animal

form.

When we need

groceries, the sanitized supermarket is our source, not the wild. But when

a brave shoots a deer, he may say, “I am sorry I had to kill you, Little

Brother. My children were hungry. My family needs your meat. See, I hang

your antlers in the tree. I decorate them with streamers. I smoke tobacco

in your memory. Each time I cross this path, I shall honor your spirit.”

We seldom talk

to our food, and even table grace is often an embarrassment to us: our

consciousness is separated from the sacred, that on which our lives literally

depend.

When a woman

in the Southwest extracts clay from the ground to make a pot for storing

food, she offers a prayer to the earth. Even stones are considered “people.”

The streams, the air, the mountains —all are alive with sacred power, and

deserve respect as our relatives, not used as objects for selfish ends,

outside of a sacred pattern of where everything fits.

The ecological

balance we need may be different than the one the hunter or the potter

knew, but the Primal religions suggest that our environmental problems

cannot be solved merely by technology.

Ancient Egyptians,

Greeks, and Romans, the more recent Maya and Inca civilizations, and the

still-persisting tribal ways in Africa, Australia, Oceana, and elsewhere

have strikingly different ways of understanding nature. For example, the

Egyptians understood the sacred in nature as stability, the Greeks as a

dynamic order, the Romans as potencies requiring compliance. But they all

have understood nature as the fundamental expression of the Holy.

Recent thinkers,

some stimulated by encounters with Primal traditions, have begun to recover

a sense of the holy in nature, including Thomas Berry, J Baird Callicott,

J Ronald Engel and Joan Gibb Engel, Matthew Fox, Roger Gottlieb, Eugene

Hargrove, David Kinsley, Delores LaChapelle, Peter Marshall, Seyyed Hossein

Nasr, Steven Rockefeller and John Elder, Charlene Spretnak, Brian Swimme,

and, of course, Pierre Teilhard de Chardin.

In sum: Our ecological

endangerment cannot be remedied by mere technology. The intimacy Primal

peoples have with nature can guide us toward healing. |

|

|

6. The Holy in

the Self

MANY ASIAN RELIGIONS behold the sacred

in the psyche. A Hindu story: In the forest ten thousand rishis worshipped

the god, Shiva, in only one, static manifestation. Shiva decided to appear,

to show them that his manifestations are multitudinous; that his personality

is many, not one; that he is motion, movement, dance.

But the rishis,

whose preconceptions were challenged, rejected him. They called forth a

great tiger who ferociously attacked Shiva at his throat. Shiva, with his

little fingernail, skinned the tiger and wrapped the skin around him as

a cloak. Then the rishis chanted a magic spell, and a great serpent

emerged from the ground and, around the body of Shiva, began to writhe

and twist and choke. But Shiva disabled the serpent, and cast its long

body around his neck as a streamer of garlands. The rishis’ incantations

finally caused a demon dwarf to attack Shiva with a mace. But Shiva placed

his little toe on the demon’s back and began to dance.

All the gods

came to see this dance, in which Shiva took every threat and made them

props in his performance, showing us that whatever comes our way, however

frightening, can be rendered harmless, even enriching, as we accept it

into our dance — now moving forward, now retreating, now high, now low:

the divine personality in many forms, always in process, moving in the

eternal dance of the cosmos.

This transforming

power within is sacred; from it arises the meaning of our lives. The many

dimensions of awareness are celebrated also by Buddhist mandalas. Even

the ferocious Buddhist temple guardian figures challenge us to observe

projections, and see that what we really fear may reside within us.

Through yoga,

meditation, rites, and other techniques for observing the Self (or, in

the case of Buddhism, the not-Self), Asian traditions (including Jainism,

Confucianism and Taoism) provide paths for release from the perils of the

ego.

In sum: The inner

emptiness and disorientation that leads to addiction, dependencies, and

prejudice can be healed by insights developed and nurtured by the Asian

traditions. |

|

|

7: The Holy in

Society

THE MONOTHEISTIC FAITHS behold the sacred

in the realm of history and covenanted community, not so much the tree

or the inner light, as in human relations. God is found in our meeting

one another. In memory the divine is recalled and welcomed into the present.

Moses, though brought up an Egyptian, felt a strange kinship with the Children

of Israel, who had been pressed into bondage. He discovered who he really

was by affirming his relationship with them, leading them out of the land

of slavery, into the holiness of freedom. The Law provided the way in which

Israel could be organized for holy living. In American Civil Religion,

that covenant is called the Constitution.

As we relieve

the suffering and oppression of our brothers and sisters, so, too, are

our own spirits liberated into the vitality of the community, submitting

to the commandments on which our lives and well-being as a society depend.

The succeeding

Hebrew prophets analyzed the historical forces acting on their nation and

discovered divine patterns which we have ignored — our news seems to fall

into pieces rather than patterns. Their prophesies were not so much prognostications

and predictions as they were social commentaries and warnings; today’s

prophets are the thoughtful political columnists and leaders of peace and

justice movements. The faith that God is working out his will for

justice is expressed in what may be the most prized document in American

Civil Religion, Lincoln’s Second Inaugural Address.

For Jews, the

holy community is the mystical Israel; for Christians it is the Body of

Christ, the Church; for Muslims the Umma; for Sikhs the Khalsa. Zoroastrianism,

Bahá’í, and other faiths have parallels. In the perverted

version of Monotheism called Communism (God replaced by economic determinism),

it is the Party which saves.

In our time,

we must develop a sense of community world-wide. From a shofar, or wherever

we hear a call to holiness, we awaken to a spiritual kinship and to duties

not just with those of like faith, but with all who live, have lived, and

will live.

In sum: Our social

disorientation and disintegration, the eviscerated sense of community,

the neglect of courtesy, the evaporation of service, and the growing

concerns for safety can be answered by a recovery and revitalization of

the Monotheistic sense of meaning in the process of history, as the human

relationships unfold in divine order.

But since most of us in this culture claim

a Monotheistic heritage, how did our sense of community become so damaged? |

Three

Signs

of

Secularism

Worship

of the “bottom line”

Separating

sexuality and spirituality

Acceptance

of pervasive violence

|

8.

Three Signs of American Secularism

Of the three families of faith outlined

and charted above, American culture has been largely shaped by Christianity,

a monotheistic tradition which emphasizes the covenanted community. Why,

then, has the sense of covenant been broken? Why has it been weakened even

in religious institutions?

Although many

believe they worship “the one true God,” our society is so fragmented that

we have a de facto abandonment of monotheism. We adore power, possessions,

pleasure — all of which may be good but become distractions when the vision

of how all things involve each other becomes lost.

The revelation

that God works through community now seems strange — from the jokes about

committees to our politics debased by special interests instead of decisions

for the commonweal. Rather than government as an expression of community,

its regulation and taxation seems to threaten the individual which has

been transformed from a public person (that is a citizen, a person

in relationship with others) into a bundle of desires for consumption.

The “happiness” of the Declaration of Independence involved the capacity

to affect communal good; now “happiness” too often means selfish satisfaction.

America is a

“case study” of perverted religious impulse. (See chart.) The genius of

monotheism — to see the sacred working through the history of covenanted

community — is distorted by self-righteousness and exclusivity that are

typical dangers of this family of religions.

In outline, here are three signs of this

secularism:

1. The Bottom

Line, severed from a sense of the larger good, seems to be our overarching

public value. The bottom line is expressed in pseudo-religious language

by Christian extremists who focus on heaven and hell. Instead of urging

us to do good because it is right, we are enticed with the promise of paradise

and threatened with the prospect of damnation for our beliefs. This

reward-punishment model has us so hooked that many people believe Bill

Gates has a right to fifty billion dollars of private wealth, even though

it was gained through immoral, and possibly illegal, practices.

We think of taxation

as something the governments do. We are not permitted to regard our contribution

to Bill’s bundle as taxation because it goes to him, rather than to the

government. He gets to decide how to spend it, not us. We have little choice

but to support his inferior products because of his predatory ways. His

philanthropy is no defense: Instead of each citizen controlling one’s money,

or being represented in government, Gates extorts and decides. It is taxation

without representation.

This is not to

judge Gates personally; but this is a metaphor for how difficult it is

to think about economic justice.

Business is often

judged not by whether society is helped but by whether riches result. We

have abandoned the idea of vocation as a role by which one contributes

to society with a wholesome service — making shoes, doctoring, producing

food, settling disputes, entertainment. A fair return on investment is

not wrong, but worshipping profit is.

2. Sexuality

is divorced from spirituality. One cannot be either fully spiritual or

sexual without being both. Even celibacy is an intensely spiritual wedding

to one’s sexual nature. The religious poet William Blake wrote of the genitals

as “Beauty,” but we regard their portrayal as pornography. What does it

mean that we accept the most appalling violence in the arena, on TV, and

on the screen but restrict the display of love-making?

3. The third

sign is violence. Violence arises from, and reinforces, the first two signs

of secularism. Separating profit from social good and dividing sexuality

from the spirit distorts relationships and twists energy into acts of malignity.

By the mid 60s,

community participation measured in many ways and documented by Robert

Putnum of Harvard, began a dangerous decline. Air conditioning replaced

the front porch swing and neighborly interaction diminished. With each

member of the family having one’s own TV, the viewing experience loses

its social dimension. The investment we made in the Interstate Highway

System could have been used instead for a public transportation system

that would have avoided minimized the destruction of neighborhoods by the

roads which divided or replaced them with the resulting social problems,

the advance of urban sprawl, and the degradation of our air and other environmental

damage. Recent popular perversions of Asian faiths also justified spirituality

as merely an inner concern.

Christianity

has moved from the understanding of the church as the “Body of Christ”

and the vision of community the Pilgrims shared to the “Sheila-ism” Robert

Bellah identifies as the isolated spirituality of our time. The theological

transformations have paralleled the technology in leading us into forms

of disconnection. Whether the holistic metaphor of the world wide web’s

interconnections will redeem the increasing specialization and cyberfication

of humanity remains to be seen.

With the loss

of a sense of bonding, even within families, we have become addicted to

violence. A typical American child sees 40,000 “play” murders and 200,000

dramatized acts of violence before turning 18. The link between the portrayal

of violence and acting out by the vulnerable is no longer debatable.

Rather than repeat

the appalling statistics, let me focus on how accepted violence has become,

so pervasive that we don’t even see it. Even gentle comic strips like Peanuts

perpetuate our culture of violence.

When I took my

son some years ago to Worlds of Fun, a place for “family entertainment,”

I discovered their video games scored by lopping off as many heads as you

could. What does it say about us that we dismiss thus as “just fun, mere

entertainment”?

The first time

friends proposed playing Cowboys and Indians, I was shocked. Why would

anyone want to play bang-bang: you’re dead just for fun? Advertisements

for games command: “kill your friends guilt free,” “get in touch with your

gun-toting, cold-blooded murdering side.” We praise the ingenuity of special

effects — violence as art — while we dismiss their impact on us, the children,

and the vulnerable. Actors, producers, and the movie companies should be

ashamed of serving their careers and the dollar by modeling violence. They

should also be embarrassed at their imaginative failure to create wonderful,

wholesome entertainment.

Our language

itself is a menace. We talk about fighting cancer more than healing. Radio

station KXTR tries to be funny by asking us to enjoy a weekend with Bach,

Beethoven, and Brahms as “the Killer B’s.” At my son’s graduation proudly

posted was the host’s school song, called — you guessed it, “The Fight

Song.” “We are the Shawnee Mission Raiders! We have the team that fights

to win. . . . Go Fight, Win!” Why not “Play Well”? Why is winning so important

that one must fight to do it? Why a school song based on such a metaphor

instead of healing or building or growing or team spirit?

We are so immersed

in violence it is hard to see its extent. Because the nature of violence

is separation, we need to discover the pattern which can heal the schisms

and bring the pieces together. |

| Religions are

alike in that they all originate from experiences of awe, encounters with

the Sacred, but the way those experiences are understood or emphasized

varies.

To blend religions together

would produce a dangerous spiritual pabulum, just as reducing the dimensions

of an amphitheater to a single point would forgo the expanses which can

contain a powerful and glorious assembly of diverse people

So how do religions fit together?

Perhaps as the length, width, and height of a room are essential dimensions

of the space, the Primal, Asian, and Monotheistic traditions we have outlined

are essential expressions of the Sacred. Each religion may have some acquaintance

with other dimensions, but as it has developed, it may become expert in

a particular expression of the Sacred.

. |

9.

Are All Faiths Really One?

We want to stop the violence we see perpetrated

in the name of religion. We think if we only recognize that all religions

are basically the same, violence will cease. It is a beguiling sentiment.

Two examples: All religions believe in God; the Golden Rule appears in

all faiths. But neither is true. While Jews, Christians and Muslims worship

one God, forms of Buddhism, Jainism, Confucianism, and Taoism are non-theistic,

and conceptions of God vary so greatly among many religions that it is

confusing to use them to support the first italicized claim. While texts

similar to the Golden Rule can be extracted out of context from many traditions,

viewing them as like ethical principles violates the integrity of the faiths

by forcing them into a Western category of thought.

Huston Smith

asks, “How fully has the proponent [of the view that all religions are

at their core the same] tried and succeeded in understanding Christianity’s

claim that Christ was the only begotten Son of God, or the Muslim’s claim

that Muhammad is the Seal of the prophets, or the Jews’ sense of their

being the Chosen People? How does he propose to reconcile Hinduism’s conviction

that this will always remain a ‘middle world’ with Judaism’s promethean

faith that it can be decidedly improved? How does the Buddha’s ‘anatta

doctrine’ of no-soul square with Christianity’s belief in . . . individual

destiny in eternity? How does Theravada Buddhism’s rejection of every form

of personal God find echo in Christ’s sense of relationship to his Heavenly

Father? How does the Indian view of Nirguna Brahman, the God who stands

completely aloof from time and history, fit with the Biblical view that

the very essence of God is contained in his historical acts? Are these

beliefs really only accretions, tangential to the main concern of spirit?

The religions . . . may fit together, but they do not do so easily.”

While the mystical

traditions within many faiths may be remarkably similar, mysticism is not

at the core of many of the world’s religions.

To say that all

religions are alike is like saying all food is alike. If I have a cholesterol

problem, have lactose intolerance, am allergic to shell fish, or observe

religious dietary laws, the fact that all food by definition is nourishing

does not enable me to eat everything. A religion may be life-giving to

one person and toxic to another. A faith that is deeply meaningful and

obviously beneficial to one person or society may be opaque or even distracting

from the path of wholeness to another.

Religions are alike in that they all originate

from experiences of awe, encounters with the Sacred, but the way those

experiences are understood or emphasized varies.

So how do religions

fit together? Perhaps as the length, width, and height of a room are essential

dimensions of the space, the Primal, Asian, and Monotheistic traditions

we have outlined are essential expressions of the Sacred. Each religion

may have some acquaintance with other dimensions, but as it has developed,

it may become expert in a particular expression of the Sacred.

To blend religions

together would produce a dangerous spiritual pabulum, just as reducing

the dimensions of an amphitheater to a single point would forgo the expanses

which can contain a powerful and glorious assembly of diverse people.

Our age is one

which, beset by environmental, personal, and social challenges, can addressed

by the special insights of Primal, Asian, and Monotheistic traditions.

We understand ourselves and our own traditions better by encountering others,

and engaging in mutual purification of the faiths through respectful exchange.

We cannot afford

to ignore their wisdom, or to live with our own so routinely that we have

lost the refreshment of the experience of awe. The peril, despite the promise

of the new millennium, is real. If we neglect any of the three dimensions

of the Sacred, civilization as we know and hope it to be will end. As the

ancient Tao Te Ching says, “Where there is no sense of wonder, there will

be disaster.”

Thus the mission

of CRES — to work with all faiths to rekindle the sense of wonder in our

overwhelmingly secularistic age. |

| Those with

faiths other than our own become our guides to a deeper understanding of

the reality beyond words on which we depend, out of which we arise, and

to which we return. |

10.

Faiths in Dialogue

The congress of the faiths can best occur

by discovery and growth within each tradition, stimulated by mutual encounter,

rather than by organizational assimilation or imitation.

Those with faiths

other than our own become our guides to a deeper understanding of the reality

beyond words on which we depend, out of which we arise, and to which we

return.

Encounter must

occur not only internationally and nationally, but regionally and locally

as well. In many communities, religious pluralism is a reality ready to

be celebrated, as it is here in Kansas City. Rather than focus on international

leaders, it may be more productive to develop exchange between and among

various faith communities within each locality. This is why CRES focuses

on our metropolitan area, though we maintain contact with international

organizations.

Because of complex and unconscious assumptions

of identity and difference within faith communities about others, it is

helpful to approach mutual study with a generalization such as the three-part

pattern here described, a generalization understood as such, with the process

of the exchange modifying, challenging, and ultimately abandoning the generalizations

as the rich texture of interfaith encounter purifies, transforms, enlarges,

and deepens the practices of the participants.

Such faith encounters,

by indirection, through conversation, visitation, common worship, shared

projects, and significant friendships, may be the best way to discover

solutions to the three crises of our secularistic age. The simple three-part

pattern we have outlined in this year-long series becomes increasingly

complex without falling into pieces. |

Appendix One:

from the Conference Declaration

Wisdom from Our Faiths Cited in 2001 Greater

Kansas City “Gifts of Pluralism” Conference Concluding Declaration:

The gifts of pluralism

have taught us that nature is to be respected, not just controlled. Nature

is a process that includes us, not a product external to us that can just

be used or disposed of. Our proper attitude toward nature is awe,

not utility. When we do use nature as we must - for food, housing,

and other legitimate purposes - we should do so with respect and care,

preserving its beauty and mindful of its connection to the Sacred and ourselves.

We have also learned

that our true personhood may not be in the images of ourselves constrained

by any particular social identities. When we realize this, out acts

can proceed spontaneously from duty and compassion, and we need not be

unduly attached to results beyond our control.

Finally, when persons

in community govern themselves less by profit and more by the covenant

of service, the flow of history towards peace and justice is honored and

advanced.

|

11.

Three Attitudes

What attitudes further such dialogue? Targeting

Jews for conversion on High Holy Days, Hindus at Divali, and Muslims at

Ramadan may appear as silly ignorance or proselytizing arrogance by those

who have tasted the fruits of genuine interfaith encounter.

Thus Pope John

Paul II, who has pursued interfaith relations vigorously, apologized for

horrors through the ages done by Christians. One evening before the negotiations

between the Israelis and Palestinians began, a panel here in Kansas City

discussed the prospects for peace. The Muslim leader began by confessing

the terrible things done in the name of his faith. The rabbi likewise enumerating

evils perpetrated by those claiming to be Jews. The audience was deeply

moved by such frank admissions. From such mutuality rather than defensiveness,

genuine encounter becomes possible. What a contrast to the schemes of conversion

some have pursued!

1. While one

can believe fervently in one’s own faith, to share it without equal openness

in encounter with another may betray unacknowledged insecurity about one’s

own religion. The idea that one religion is so superior to all others that

all should convert to it fails to acknowledge that most of us follow religious

paths shaped by the times and cultures in which we have been born. Most

Indians are Hindu. Most Saudis are Muslim. Most Americans are Christian.

Even those who adopt a different religion do so usually because of

the lens of exposure.

2. The attitude

that all religions are the same at core is also not the most helpful position

for honest dialogue. "Any attempt to speak without speaking any particular

language us not more hopeless than the attempt to have a religion that

shall be no religion in particular," said Santayana. To say all religions

at their core are the same is to say that all languages are fundamentally

identical. But since most of us are unfamiliar with many faiths, this is

not obvioius; and with a good heart and sincere intent, we look to confirm

our presumption; and in an effort to accommodate one another, it is easy

to edit differences out of our conversation and distort things to regard

them as similar.

3. If we begin,

however, as explorers, without too great an eagerness either to sell or

to buy, we can make great discoveries about our own traditions and those

of others. We may find that our faiths historically have often influenced

each other to such an extent that we may see all of us engaged in one rich

religious adventure rather than completely distinct revelations. We may

find that our common problems today — in the environment, in the personal

realm, in the human community — can draw us into deeper understanding of

the sacred, so that our attitude becomes one of mutual ownership of each

others’ traditions without losing our own paths, just as we all own the

highways of this nation even though we live on our own street. We may find

that the many paths lead us not to a single sacred spot, but to many manifestations

of the holy, from which our service to others as kin may abundantly flow.

Such awareness

may help to purify and mutually transform us into that greater witness

by which the seductive powers of secularism may be healed. |

Appendix Two

Four Levels of Engagement

1. Many people now know the dangers of

religious prejudice. They believe that everyone has the right to one’s

own religion, or none. This is the first, most superficial level of engagement

with other faiths. It is an advance from the days when people were forcibly

converted to another faith or denied opportunities because of their traditions.

Home associations can no longer prevent Jews from buying in their areas.

While Wiccans and other minorities still encounter discrimination from

time to time, we have come a long way.

But are their deeper levels

of engagement with faiths other than our own?

2. We can move from respecting not

only others’ right to their own faiths to respecting their faiths as well.

This is a subtle but crucial distinction. It is one thing for me to agree

you have the right to have whatever painting you wish in your living room,

and it is another thing for me to learn why it is beautiful to you, even

if I do not want it in my living room.

3. We take another step toward deeper understanding

when we participate in interfaith exchange. I need a mirror to see myself.

When Christians discover why Jesus is so revered by Muslims, when Tibetan

Buddhists and Jews tell their stories of suffering, when Hindus and American

Indians share dances, all can see their own heritage more clearly with

the mirror of the other.

4. But there is an even fuller engagement.

The mirrors of faith transmit and reflect the holy from many angles. Bringing

and focusing them together, a powerful, curative light can shine to heal

the three great crises of secularism: we can apply the wisdom of the world’s

faiths to the endangered environment, the violation of personhood, and

the broken community.

Is this the key religious task of the new

millennium?

|

12.

Finding the Treasures

Rather than threaten, differences can enrich.

How? By disclosing ourselves as well as giving us a clearer sense of the

diversity within the Infinite. While we can never fully escape from the

limited, the partial, the secularistic, the world’s great religions arise

from the whole, from experiences of awe and participation in the vitality

of the cosmos, from the deep questions — “What is so important that my

life depends on it or that I would die for?” and “What may I do to honor

and share it?” In other words, “What is sacred?”

The answer to

this question may come from one’s own tradition. Yet we need the help of

others to find that answer in this secularistic age. “He who knows one

religion knows none,” said Max Müller, suggesting that until we can

view our own faith from the perspective of others, we cannot know our own.

The import is similar of Kipling’s question: “What knows he of England

who only England knows?” I know what Kansas City is better by acquaintance

with San Francisco and New York and Delhi and Rome. The paradox of these

teachings is the key to understanding a favorite story of my teacher, Mircea

Eliade:

A pious rabbi named Eisik once lived in

Cracow. He was very poor. One night as he slept on the dirt floor

of his hovel, he had a dream which told him to go to Prague, and there

under the bridge that led to the royal castle he could unearth a great

treasure. The dream was repeated a second night, and a third.

He decided to

set out for Prague. After many days walking, he entered Prague, and found

the bridge that led to the royal castle. But he could not dig. The

bridge was guarded day and night. The rabbi walked back and forth awaiting

a moment when the bridge might be unwatched and he might dig for the treasure.

The captain of the guard noticed him, and went up to him. “I’ve noticed

you walking about here these several days. Have you lost something?” At

this, the rabbi innocently narrated his tale. “Really,” said the captain

of the guard, who was a secularistic, modern man, unconnected with his

dreams, “Have you worn out all your shoe leather merely on the account

of a dream? I too have had a dream, three times, which told me to go to

the town of Cracow, and look for the rabbi Eisik, and dig in his dirt floor

behind his stove in the middle of his room, and there I would find a great

treasure. But dreams are silly superstitions.”

The rabbi immediately

understood and promptly returned home, entered his hovel, and dug

underneath the heart of his hearth, where the warmth of his own being lay.

And there he unearthed a treasure, which put an end to his poverty.

From this tale Eliade draws two lessons.

The first is that the treasure which can put an end to our spiritual poverty

lies not in another country. It can be found within the heart of

our heart, the center of our own tradition. In the house of ourselves

it lies buried in our innermost being. The second lesson is the paradox:

only after a pious journey to a distant region, in a strange country where

someone speaks to us in a foreign accent, can we be directed to the location

of that buried treasure.

Through encounters

we have with the strangers of other faiths we can discover our own faith.

Through a far pilgrimage we can know ourselves and our home and be saved.

It is through the mutual purification of faiths meeting each other that

the Three Crises of Secularism can be healed. The religions of the world

fall not into pieces but compose an infinite pattern. |