|

|

TEXT of UNITY MAGAZINE article in 2011 Mar/Apr issue

Harmony in a World of Differences:

Interfaith Works

by Vern Barnet

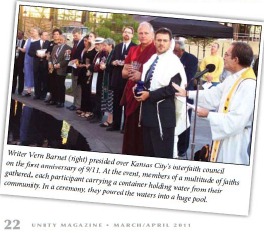

Text of inset photo caption: Writer Vern Barnet (right) presided over Kansas City's interfaith council on the first anniversary of 9/11. At the event, members of a multitude of faiths gathered, each participant carrying a container holding water from their community. In a ceremony, they poured the waters into a huge pool.

You are a Muslim male, born abroad. You chose American citizenship decades ago and have worked here with many religions for years. When Christian churches in the South were burned, you helped raise money to help rebuild them. You’ve volunteered for humanitarian relief missions around the world, including Bosnia, Iraq, and Afghanistan.

Now it is September 11, 2001. From emails, you know of Muslims in other cities who have been threatened and attacked. You hesitate to answer the phone, but you do. A Jewish acquaintance says he’s calling to be sure you’re OK and asks if there is anything he can do. Your anxiety turns to awe at the thoughtfulness of your acquaintance.

A couple days later, you get a another call, this one from the local Interfaith Council. You are asked to join a senior Christian minister and a prominent Jewish rabbi to present greetings at Sunday afternoon’s metro-wide emergency gathering of faiths from A to Z, American Indian to Zoroastrian, an observance of “Remembering and Renewing” the community’s commitment to safety for all faiths. That day you see hundreds of fellow Muslims in the huge auditorium and know that this is the first time in five days that some have dared to leave their homes.You are a Muslim mother, born in this country. On 9/11, grade school classmates tell two of your boys, both Scouts, that their father is a terrorist. Before long you decide to leave your job as vice-president of a Catholic hospital where you are much loved in order to help others understand your faith.

For the first anniversary of 9/11, you work with the Interfaith Council, civic organizations, and scores of cooperating congregations in a day-long observance. Before dawn, members of every faith gather in a park containing a marker with the First Amendment between City Hall and the Federal Justice Center. At sunrise, a brass ensemble from the Kansas City Symphony begins a ceremony in which the faith representatives pour waters from their communities, from the rivers, lakes, and oceans of the world, and from the famous fountains of Kansas City, into a huge pool, to cleanse participants of prejudice and purify community intentions.

With police escort, the group walks through downtown to the Cathedral where the names of those who died are read all afternoon. That evening, the governor and his family arrive and Jewish and Muslim children begin the ceremony by singing songs of peace together, and the Kansas City Ballet and a voice from the Lyric Opera assist in interpreting the meaning of the day. The mayor speaks, music from around the world is performed, and the mingled water blessed by all is apportioned back to each community as a sign that faiths are gifts to each other, with distinctions cherished.

Three years later, your husband goes on the Hajj, the pilgrimage to Mecca, a duty of each Muslim to fulfill before one dies. With the millions of others as is the custom, he wears a white burial shroud symbolizing the equality of everyone under God and the resurrection of humanity. He returns home, joyful and radiant. But in a few hours, he is dead. At an interfaith dinner with 500 guests you have helped plan, a Jewish friend announces the reason for your absence.

At the funeral the next day, Muslim leaders officiate with Jewish and Christian speakers. American Indian, Buddhist, Sikh, Hindu, and mourners from other faiths as well overflow the chapel.

Then to the cemetery. On a ladder your two older sons climb down into the deep grave and lovingly place their father into the ground, wrapped in the very garment, white, that he wore on the Hajj. Others from every faith help with the burial by placing clods of earth into the grave and waiting in the cold until the bulldozer completed the task and closed the grave. The crowd was struck with the awe from which every faith arises.I have a thousand stories of such comfort because interfaith friendships flourish. I’ve told of two Muslims because their faith is slandered most; but here, in our expanding interfaith community, each faith is protected, honored, and cherished.

I don’t have to spell out for you how individuals and our community find healing and strength through such friendships, deliberately created and nurtured. When friendships replace suspicion, and joy in diversity erases self-righteousness, our own faiths are deepened and polished by rubbing up against the others as we see the light of our own traditions reflected in theirs.

For a TV special in 2002, CBS came to Kansas City to see how we have learned to love one another. In 2007, Religions for Peace-USA at the United Nations Plaza and Harvard University’s Pluralism Project sought a town for their first national interfaith academies. They selected Kansas City for the term because we offered the enrolled professionals and students hospitable Orthodox Christian, Muslim, Sikh, Jewish, and Buddhist congregations to visit, and speakers from other traditions as well.

A Harvard researcher said, “At the Pluralism Project, we consider Kansas City to be truly at the forefront of interfaith relations.” I believe one of several reasons for this is the proximity and influence of Unity, which has, since the time of Charles and Myrtle Fillmore, validated wisdom found in faiths around the world.

But while friendships and social comity are perhaps the readiest reasons for the interfaith enterprise, our desacralized culture itself requires healing. We need to recover the sense of awe that leads to gratitude, and the gratitude that matures into service. The Tao Te Ching warns, “Where there is no sense of awe, there will be disaster.” Greed, exploitation, and the lust for power crowd out awe. But Rumi writes, “Awe is the salve that will heal our eyes.”

The disease of our desacralized culture presents three symptoms: our environmental crisis, the uncertainties of personhood, and a destructively partisan society. We need the wisdom stimulated by interfaith encounter, sharing times of awe, to bring about healing.

In Primal faiths (American Indian, tribal African, and Wicca are examples) we find ecological awe as we learn that nature is to be respected more than controlled; nature is a process which includes us, not a product external to us to be used or disposed of. Our proper attitude toward nature is wonder, not consumption.

In Asian religions (such as Hinduism, Buddhism, Confucianism, and Taoism) we rediscover the awe of true personal identity as our actions proceed spontaneously and responsibly from duty and compassion, without ultimate attachment to their results.

In Monotheistic traditions (including Judaism, Christianity, and Islam), the awesome work of God is manifest in history’s flow toward justice when peoples are governed less by profit and winning and more by the covenant of service.

The interfaith promise is nothing less than the restoration of nature, the recovery of the whole self, and the life of a community of love.

Religious pluralism is gift, not a threat. We will perish without this gift. This gift is the gate that opens a path of healing hidden from previous generations. Our troubled and fearful world is looking for this sacred path of awe.copyright 2011 by Unity Magazine and Vern Barnet

Kansas City, MO

The Rev. Dr. Vern Barnet, who writes about interfaith friendships on page 20, founded the Greater Kansas City Interfaith Council in 1989. Barnet, a former member of the Unity Magazine editorial board, writes a weekly column for The Kansas City Star, has taught at several seminaries, and received numerous civic and religious awards. For further keys to interfaith understanding, visit www.cres.org/keys.