#211204

The birth of joy in a landscape of sorrow happens only in the heart. The landscape may have a long distance and a wide horizon, but the heart is within, and infinite. The journey may take a very long time, but the heart discovers eternity. The passageway may be dark, but the heart is luminous. The nourishment may seem meager, but in the heart it is a feast. In the heart, all things become gifts; the heart is the realm of redemption. Living in the heart of God, all things are holy.

TITLE SUGGESTION:

POSSIBLE SUMMARY:

I see crowds of young people arriving at a nearby church as I walk to the bus stop on my way to the Cathedral Sunday mornings. I admire this thriving church’s ministry to my neighborhood. Doing interfaith work in the community for 35 years convinces me that there ought to be different churches because people have different needs. Different religions are gifts to us, not threats. Still, I doubt that most young people, whether they attend church or not, are conscious of how our culture frames religion and limits their ways of accessing the most sacred treasures of faith. I worry that we Episcopalians are unintentionally hiding the treasures we cherish. I reckon a good number of the young people I see would be astonished and grateful to learn about our evolving Episcopalian tradition. 1. Cultural framing To most media, religion is regularly told as conflict, abuse, and other forms of oppression, and even anti-science. I need not give examples. The “nones,” the expanding number of folks with no faith affiliation, often explain their rejection of organized religion with a sense of righteousness, unsullied from the institutional corruption the media report. “I can be spiritual by myself,” they sometimes claim. Many “nones” reject religion because they find it incredible, superstitious, or repulsive. “Do you really insist that God sent those Ten Plagues to the Egyptians and killed their innocent firstborn children and animals?” For some who do go to church, the motivation is personal guilt, or to make or connect with friends, to enjoy musical entertainment, and so many other reasons. One of my students wanted to survey his church to find out why people attended. He received answers such as the church is nearby, the windows are pretty, the preacher is friendly, the grandmother helped found the church — none of the responses concerned the stated beliefs of the church. Which is profoundly ironic since most people associate religion with beliefs. When I was asked by the Kansas City Star to write a weekly religion column (which I did for eighteen years), my column’s name was “Faith and Beliefs” even though I told my editors beliefs are not important in most religions. For example, to be Jewish, you don’t need to believe anything. You can be a good Jew and an atheist. You simply need to have a Jewish mother. You can believe in one god, or no god, or 330 million gods and be a good Hindu. The Buddhist Heart Sutra denies the basic doctrine of the Buddha to teach that what is important is not belief but practice. Scholars sometimes identify dimensions of religion with four C’s: Creed (belief), Cultus (rituals), Community, and Code (moral expectations). Different faiths and different adherents may emphasize one or two of these dimensions over others. Nonetheless, the persistent modern framing of religion as belief is, in my view, problematic. 2. The Sacred Story As the great late sociologist of religion Robert Bellah, an Episcopalian, has demonstrated in a lifetime of scholarship, religion is about a sacred story. Most scholars, I think, agree. The four C’s are ways of understanding, reenacting, sharing, and behaving in harmony with the story. Since the time of the first Book of Common Prayer, 1549, the meaning of “belief” has changed. Then it meant something more like “trust” or “commitment to.” When a husband says of his wife, or a producer says of one’s actor, or a partisan says of one’s candidate, “I believe in her,” this is not so much a factual statement as a declaration of relationship. “Belief” derives from the same Latin root as libido, desire, and is akin to the German liebe, beloved. It’s not about facts. It’s about a bond. When I say I believe in Jesus, I am not affirming any historical or theological speculation; rather, I am belonging to Him. Instead of a virtual faith confined to a compartment of my mind with answers to theological questions, Jesus becomes the Bread and Word for my whole life. The 20th Century Anglican poet T. S. Eliot theorized that the power of 17th Century poets like John Donne, Dean of St. Paul’s Cathedral, is in part due to the fact that they wrote before the “dissociation of sensibility,” when thinking and feeling were still united. Then belief and be-love were the same. Believing in the Christian story is not singularly an intellectual decision. When I recite the Creed, I am outlining a cosmic story of salvation in which I am involved, not a scientific proof. (The Latin word credo has many meanings including “to entrust.”) Belief in the shallow sense of cerebral assent hinders us from understanding who we are from stories. This is so, even of fiction. Anglicans defended the fiction of Elizabethan theater against the Puritans who decried the stage because it was not true. The enjoyment and benefit of fiction, from Aesop’s fables to your favorite movies, arises from encountering them with a “willing suspension of disbelief,” in the phrase of Anglican poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge. Another Anglican poet, W. H. Auden wrote, “It is as meaningless to ask whether one believes or disbelieves in Aphrodite or Ares as to ask whether one believes in a character in a novel; one can only say that one finds them true or untrue to life. To believe in Aphrodite and Ares merely means that one believes that the poetic myths about them do justice to the forces of sex and aggression as human beings experience them in nature and in their own lives.” Our story is genuine, and we participate in it and are formed by it. The Palm Sunday parade, the Maundy Thursday washing of feet, and the Good Friday adoration of the cross, as examples, are no more superstitious than a client following a therapist’s suggestion to “place your deceased mother in this chair and tell her how you miss her.” Neither is about facts so much as about a relationship which ritual appreciation or therapeutic methods may deepen. So we can tell that story of the Ten Plagues of Egypt as a spur to our evolving questions about how to live in the light of the Gospel. 3. What Episcopalians Can Offer To the “nones,” we can offer a spiritual reframing service. We can replace a superficial, virtual frame of religion with what is genuine. God is not a HD display idea; God is reality. Over the virtual we choose embodiment. Christ is incarnate. Religion is less as an inventory of disputed facts and more as a sacred story. Instead of religion focused on concepts, we offer a faith embracing and balancing creed, cultus, community, and code, each dimension of the holy narrative. Since becoming an Episcopalian seven years ago, I’ve often visited with young people about what they desire in religion. From these conversations I am convinced our living heritage offers what the future needs. Reframing is a first step. Young people want to participate, to belong, in an open tradition that requires something of them, something like the ancient meaning of “belief.” In a future article, I’ll suggest how our tradition of table and word offers fulfillment, but the way we present our faith may yet be clarified and our mission in the Jesus Movement enhanced. --

Can Knowing Other Faiths Deepen Our

Own?

It’s an affair of the heart. You meet these compassionate people doing good things. You want to know them, to understand the faiths that give their lives meaning. They are not Christian. You remember Jesus told about a Good Samaritan who worshipped in a tradition other than His own. Such people are the best answer to the question, “Can I learn about other religions without watering down my own Christian beliefs?” I’m old enough to remember the days when folks were warned, and even prohibited, from worshipping with others. We’ve come a ways toward tolerance, but we have a long way to go before we see religious pluralism as a gift, not a problem, a blessing, not a threat. The political use of religious prejudice darkens the world and demeans the religious urges in every human being, and deprives us of many of God’s gifts. “He who knows one religion knows none” declared Max Mueller, a 19th Century scholar of comparative religion. To make the same point, I slightly paraphrase Rudyard Kipling: “What knows he of England who only England knows?” We understand our own country better by traveling abroad. We know our own town better by having visited other places. We grasp own faith more securely by encountering and learning from others. Anglican T. S. Eliot wrote what many regard as the most profound Christian poem of the last century, “The Four Quartets.” Eliot read several languages, including Sanskrit. His poem draws upon not only Christian mysticism but explicit Hindu teachings to illumine both. I thought I knew what church bells meant. Bells routinely say, “The service is about to begin.” I heard them here; I heard the cathedral bells in Europe. In fact, I had the job of ringing a chapel bell when I was a student. But as a young man visiting Japan, at a Shinto shine, I saw a child swinging a rope with a striker at the high end to hit a gong. I learned that the noise was intended to awaken kami, the divine, so that kami would pay attention to the devotee. Paradoxically the noise awakens the devotee to the presence of kami. What seemed like a silly, even superstitious, act of waking kami was in fact how kami awaked the devotee. In a fresh way I saw that the church bell does not merely call us to church, but also can awaken the presence of the sacred in us; the bell is not just an external ringing but also an internal resonance. It is not a Pavlovian alarm compelling us to go somewhere; it is rather a signal awakening us from self-centered slumber. Let me move from that childish awakening to three examples of how my Episcopalian faith has been enriched by knowing something of other traditions. 1. Christianity and Buddhism Perhaps one of the most important sustained interfaith dialogue of our time was begun between Christian and Buddhist monastics. What two religions could be more unlike? Christianity proclaims a Creator God while Buddhism instead speaks of Emptiness, the Void, with no beginning, no Creator, only ongoing, interrelated processes, none of which rules without being ruled. Even more strange is how the two faiths understand personhood. Christianity assumes we are individual souls, each with one’s own eternal destiny. Buddhism denies the soul as a separate and everlasting personal existence. With such striking contractions, what’s there to talk about? The monastics discovered they could talk about their experiences. From such conversations, the Christian practice of Centering Prayer has been rediscovered. While the language and images differ in each tradition, the differences themselves illumine the similarities. When Meister Eckhart (1260-c1328) said, “I pray God to make me free of God,” was he pointing to the Buddhist experience of the Void? Is the Void a way of being alert to the dangers of defining and limiting God by our own conceptions? Does this bring us back to that enigmatic answer when Moses asked for God’s name, and God said something like, “I will be what I will be”? Can we look at our own scriptures in a new light? As for the Buddhist teaching that the self is empty, consider Philippians 2:7: “Jesus emptied Himself” that he might reveal God’s glory. If Jesus is our model, then must we not also empty ourselves? Can we use Buddhist skepticism about selfhood to advise us to look at our tendencies toward self-centeredness? 2. Christianity and Confucianism I like to think that the Anglican style is a Confucian form of Christianity. Both traditions lay importance on education and emphasize the unifying beauty of ritual as a way of honoring and experiencing the sacred. Some years ago I was in San Francisco during a Chinese New Year parade. Large inflated plastic sages bowed endlessly from pulled strings like giant puppets atop the floats. That’s the problem with Confucianism, I thought: insincere show, people being polite even when they despise each other. But I’ve come to see that sometimes acting with courtesy can actually can arouse a more generous attitude toward others. Even if we are moody, observing the forms of etiquette guards us against offending others and thereby protects us from others reacting against us. We don’t want to infect our friends with disease; why infect them with the vagaries of our emotions? (Of course those closest to us deserve to know how we are doing, but we don’t have to tweet it to everyone we’ve ever met and hope to meet.) Social and liturgical rituals do not depend upon transient feelings. Rituals remind us that feelings are for feeling, but we need not make decisions based on them. Rituals enable us to practice the way we really want to be. The sharing of God’s abundance with others in the Eucharist is a model for how we want to live our lives, beyond our momentary failures to perceive God’s constant grace. Confucianism became rigid and unable to adapt to changing environments. It is an object lesson for us to be sure that our rituals remain living expressions of Christ’s love, and not dead letters and futile forms, monuments which have lost meaning. Yet the impulse of Confucianism remains salutary. 3. Christianity and Islam Our Christian indebtedness to Islam is untold. Here l can only hint of why it can help us renew our own faith. In today’s culture, Christianity has often become a form of narcissism, sometimes expressed as “I believe in God, but I don’t need a church for me to know Jesus.” But we believe that the Church is the Body of Christ. United as one body, our life together forms us into the life of Christ to do God’s will. We together create or destroy the social conditions for the kind of life God wants for us. No major religion today is clearer than Islam that we as individuals affect each other. Sharia, so terribly misrepresented in the media, is really the directions for a society of justice and peace. Islam’s teachings about how we best relate to each other can enable us to recover insights within our own tradition that strengthen our faith and witness. By making friends with those of other faiths, we also refresh the wisdom and the heart of our own. Vern Barnet’s latest book is Thanks for Noticing: The Interpretation of Desire. He previously wrote for The Kansas City Star.

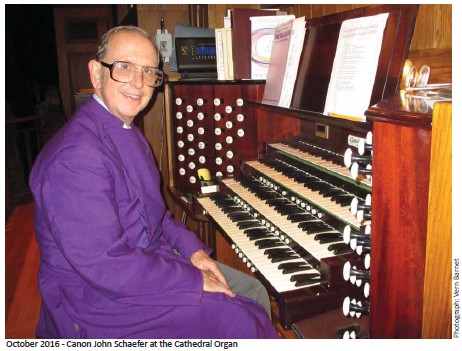

<12> 2016 December, pages Cathedral Music Director John L. Schaefer Retires As he retires, the Cathedral’s Canon

Musician sees 40 years of “growth and hospitality.”

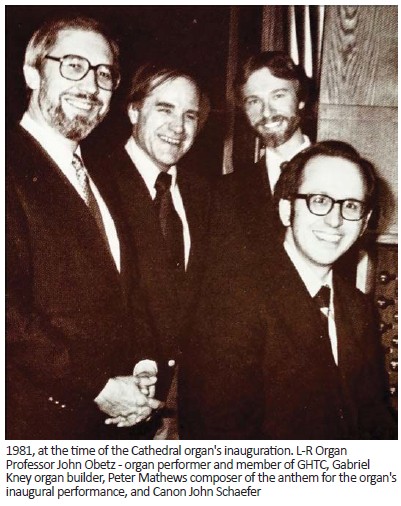

For 40 years, with four deans and various interims, Canon Musician John L. Schaefer has enriched the worship of God through music at Grace and Holy Trinity Cathedral, and enhanced the arts community in the region with devoted attention and support. His first Sunday service was Oct. 3, 1976. This year, on Dec. 31 after the 5:30 New Year’s Eve service, he retires as director of music, organist, and choirmaster. [1. How I got acquainted] Before I ever thought to become an Episcopalian, I knew John’s reputation and had attended musical events at the Cathedral. In 2001, watching TV at home, I was struck with the beauty of the national network CBS-TV broadcast of the Christmas Midnight service from the Cathedral. Shortly thereafter, I met John. The Kansas City Interfaith Council, which I then led, decided to prepare a religious observance for the first anniversary of the 9/11 terrorist attacks. Working with Mayor Kay Barnes, the United Way, and other organizations, we wanted a downtown center for the metropolitan-wide effort, which eventually led to a series of activities which began before dawn and ended after dusk at the Cathedral. The final major event, coordinated with over 50 other religious sites throughout the metropolitan area, was an evening observance attended by the Missouri governor and other dignitaries. John’s advice and cooperation were invaluable. Without them, and the reputation he had built, we could not have begun the evening with a choir of Jewish and Muslim children, included other music from Hindu chants to jazz, and garnered the participation that day from the Kansas City Symphony, the Lyric Opera, and the Kansas City Ballet. Later, national CBS-TV again chose to broadcast a portion of that evening’s observance at the Cathedral. In 2010 I started attending the Cathedral regularly. The quality of the music — voluntaries, anthems, Anglican chants, and hymns — helped me to understand the liturgy and Scripture in ways far deeper than my theological training had offered me. Later that year John asked me to select and read texts interspersed with a hymn-sing with famed organist Gerre Hancock. I suggested including texts from world religions and John enthusiastically agreed. The following year John was one of my baptismal sponsors. The many who know John have personal stories of how they came to cherish John. Choir members speak not only of his musical expertise but his help in their personal lives. [2.] John’s preparation and call John received his Master of Sacred Music degree from Union Theological Seminary where he studied theology, liturgy, and music — voice, organ, choir directing, and “all things that any musician working in a church would want to know,” he told me. Then he spent a year in London at the Royal Academy of Music, followed by two years on the staff of the famous New College Chapel at Oxford. The choir was part of the founding of the college in the 14th Century. When I asked John what he learned there, his immediate and enthusiastic answer was, “Anglican chant! — and English church music generally.” John said that Anglican chant should flow like Gregorian chant but with more inflection according to what the text says. By matching the natural speech rhythms of unmetrical texts to elastic melody lines, psalms and canticles can be elevated with the mystical power of chant. Add to that the choir’s harmony and John’s often ingenious organ illustrations of the texts. I mention this because from my first visit to the Cathedral, the chants intrigued me and give me a sense of “praying the psalms” I had never imagined before. It wasn’t long before I met with John and asked him how it worked, and later John taught me enough to do Morning Prayer. When Dean Earl Cavanaugh, of blessed memory, called John to the Cathedral, the first assignment was to repair the boys’ and men’s choir. But John accepted only with the understanding that the inadequate organ would be replaced. This involved reconfiguration of the chancel and chapel, and the addition of a balcony for the new organ designed and completed five years after John arrived. Member John Obetz, of blessed memory, internationally-known through his weekly radio program, inaugurated the new instrument in 1981.  [3.] John’s [ministry] work The Gabriel Kney instrument was the first major organ in the area with tracker key action. With John at the console, it set the standard for later organs, including the Julia Irene Kauffman Casavant Organ at the Kauffman Center for the Performing Arts. John oversees other Cathedral instruments. I count a chamber organ, three Steinway pianos and one Yamaha, one harpsichord, an impressive set of hand bells, and an electronic carillon sounding like real bells which I love to hear when I walk to services.

Guest singers and instrumentalists often enrich the service. At Easter, for example, a brass choir and timpani join the organ to celebrate the Resurrection. The endowed Curdy Scholarship brings another musician to the Cathedral, lucky to study with John. Composers have written specifically for John and the Cathedral. The choirs now include the Tallis Singers, the Trinity Children’s Choir directed by Linda Martin, the Cathedral Chorale directed by Dr. William Baker, the Cathedral Bell Ringers, and the Trinity Choir, which sang in residence in Europe in 2001, in Great Britain in 1991, 1995, 2006, 2013, and 2016, and has sung at the National Cathedral and the White House. John especially cherishes the 1995 residency at Westminster Abbey, and this past summer with a week each at Exeter and Norwich Cathedrals “because we are older and wiser and better at it.” Under John, a tradition of the “the Kirkin’ of the Tartans” with the St. Andrew Pipes ? Drums has developed into a much-loved celebration of the feast of Samuel Seabury, our first American bishop, consecrated in Scotland. A pillow to which tartans are attached is processed with music to the chancel where it is “churched.” John developed jazz services beginning in 2007. Drawing on community resources, hymns and other music have been shaped to support the liturgy and the lectionary readings. Through his musical leadership, John has nurtured a covenanted relationship with the nearby Roman Catholic Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception. In 1989, at the invitation of Cantor Ira Bigeleisen at Beth Shalom Synagogue, Cathedral choir members joined with others in the community to sing Mendelssohn’s “Elijah,” beginning a series of annual Harmony Choral Celebration Concerts, uniting religious and racial communities, at the time the only known such interfaith effort. Some of the singers from other congregations could not read music, but John was “glad to teach them because it was a rare, rich experience.” John and Leona, his wife, attend an amazing schedule of musical offerings. Their support and frequent reminders to their email list of musical opportunities have endeared them to the musical community, and encouraged many organizations to use the friendly Cathedral for rehearsals and performances. Patrick Neas, who writes the classical previews in The Kansas City Star, told me, “More than any other church musician in town, John Schaefer has made the greatest impact on the arts community at large.” I asked John how he would like his tenure to be remembered. “As a time of growth and hospitality.” Vern Barnet’s latest book is Thanks

for Noticing: The Interpretation of Desire. He previously wrote for The

Kansas City Star.

What could mysticism mean for

you?

In my first year of graduate school, I knew everything, pretty much. I certainly knew about religious types because I had read the William James classic The Varieties of Religious Experience and found its mystical, inward focus wanting. Religion, I thought, is not so much about unverifiable, ineffable, and transient private moments as it is about bringing justice to a corrupt and oppressive social order. 1. Mysticism and Social Justice So I was surprised when I was waiting in a dinner line, unaware that the person in front of me was the retired James Luther Adams, whose prophetic writing I admired but, really, little understood. Over his career Adams had taught theology at both the University of Chicago and at Harvard. Aside from his ideas, his influence could be measured by his vastly expanding those schools’ library collections in the field of social justice. Somehow, in expressing my delight in finally meeting him, I made a condescending comment about mystics as I thought to reflect his viewpoint. “But I am a mystic,” he said. “You cannot separate the mystical from the prophetic and the sacramental. Anyone of these three elements of religion alone can become demonic. A mystic does not separate himself from the world to heal people and better their circumstances.” As we sat down to eat, he told me of a monk who, while others were away on an errand, prayed in his cell. Suddenly he was caught up in a mystical rapture as never before. Then the monk heard a rapping at the monastery door. The monk did not want the interruption. If he left his kneeler, would he would lose the precious ecstatic vision absorbing him? But he went to the door, gave generously to the beggar from the pantry, and returned to his kneeler. The rapture continued as before, but with the divine voice, “Had you not fed Me, you could not have enjoyed My presence.” Dr. Adams set me straight. Later it became obvious to me that figures like Gandhi and Martin Luther King, Jr. found their passion for social justice in a mystical vision of God’s infinite love. The disciplines of public comportment in which they trained their followers were rooted in their unverifiable, ineffable, and transient private moments. While I cannot write of all who are called mystics, many seem not to be ascetics or permanent recluses. Teresa of Avila and John of the Cross, for example, were busy with institutional reformation. Bernard of Clairvaux was deeply involved in ecclesiastical and international politics. Hildegard of Bingen was a polymath, healer, and organizer concerned with justice. Even the anchoress Julian of Norwich provided advice to those seeking it from her window onto the world. Francis of Assisi traveled widely. Finding the Perfection between neurotic attachment and uncaring detachment, Meister Eckhart was drawn to pastoral care and organizational repair. He influenced Nicholas of Cusa who should be better known. One of Cusa’s mystical books, De Docta Ignorantia (Of Learned Ignorance) demonstrates that the more we know, the more we know we don’t know, a truth that can lead us to God. He became a cardinal, was involved in interfaith concerns, and argued, a century before Copernicus, that the earth is not the center of the universe. 2. Types of Mystical Visions I keep learning. The Sophia Center sisters at Mount St Scholastica in Atchison ask me to teach world religions to their spiritual direction students. During one visit some years ago I found at my bedside The Protestant Mystics (1964) with an introduction by Anglican poet W. H. Auden. It seemed a kindly plant since I had been talking about becoming an Episcopalian. Among the writers excerpted in this volume are Anglicans John Donne, George Herbert, Henry Vaughan, Alfred, Lord Tennyson, T. S. Eliot, and C. S. Lewis. Auden’s witty 12,000-word essay notes that one may prepare for, but cannot compel, a mystical experience. He contrasts the two Western branches of Christian mysticism: “The language of the Catholic mystics shows an acquaintance with a whole tradition of mystical literature, that of the Protestant is derived almost entirely from the Bible.” This marks the Catholic mystic as a “professional” writer, and the Protestant an “amateur.” The virtue of the former is technical precision; the latter has a freshness of expression. Auden identifies four types of mystic visions: (1) those involving nature: the ocean, mountains, trees, flowers, or such; (2) those arising from a transcendent, erotic love for another human being with sexual interest always subordinate to the awe and reverence in which the beloved is held (he cites Plato, Dante, and Shakespeare); (3) those involving not a single person, but many people, which he describes as agape, an overwhelming love for others; he cites the Pentecost outpouring as his first example, and admits that such an experience with a group of friends led him back to the Church; and (4) those in which God is directly encountered. Of the last, he complains that some who work tirelessly for others receive little notice, but someone claiming a particular fever may be unduly celebrated. He quotes John of the Cross: “All visions, revelations, heavenly feelings, and whatever is greater than these, are not worth the least act of humility, being the fruits of that charity which neither values nor seeks itself . . . . Many souls, to whom visions have never come are incomparably more advanced in the way of perfection than others to whom many have been given.” 3. The core of mysticism Auden fails to mention Anglican Evelyn Underhill whose 1911 Mysticism remains a classic, or Aldous Huxley’s 1945 The Perennial Philosophy. Since then, many studies of mysticism have appeared, but mysticism’s confusion with magic, asceticism, esotericism, and with paranormal, sensory-deprivation, drugs, and other non-rational experiences is yet to be clarified. I certainly am in no position to define what mysticism means, but I know what I would like it to mean. I’ll back into that by citing Huston Smith who ascribes to the monotheist the statement that “there is only one God” and to the mystic “there is only God.” Other traditions use different language to express the apprehension of a reality beyond distinctions. Buddhists prefer to speak of the “not two,” to avoid saying “one.” “One” contrasts with ordinary fragmented experience, the mystical and the ordinary making two categories, defeating the claim that there is but “one.” Christian mysticism is more than an intellectual claim that “there is only God.” It is a heart experience which radically surpasses our ordinary perceptions that things are separate from God. Putting that experience into words can verge on heresy since we usually distinguish between good and evil, between God and the world, between the self and God. But who wants to charge a mystic with heresy when sacramental and organizational commitments, or, in the modern context, concerns for social justice, are inseparable from the vision? I’m no longer a student who knows pretty much everything. So I cannot say what mysticism is, but I admit what I would like mysticism to mean: the overwhelming and self-validating conviction of divine love — palpable in awe, gratitude, and service. In your own journey of faith, what could mysticism mean for you? Vern Barnet’s latest book is Thanks for Noticing: The Interpretation of Desire. He previously wrote for The Kansas City Star.

<10> 2016 August, pages 8-9 DOWNLOAD PDF FROM PRINT VERSION Loving the World as God Loves the World Our desires to save the world, on one hand, and to savor it, on the other, can be reconciled only in God’s love. “How have you changed since you became an Episcopalian?” a dear friend asked me. He knew about my life-long and career-filled interest in world religions. He knew I still cherished Buddhist, Muslim, American Indian and other spiritual paths. 1. Closer to Tears My friend knew I do not approach world religions “cafeteria-style,” choosing this feature from one religion and that idea from another. I embrace each faith fully. One can relish both Rembrandt and Mapplethorpe, and find enchantment in both the Parthenon and the Taj Mahal. One is not violated by enjoying both a Mozart opera and a tune by Steely Dan. Somehow I’ve escaped the literalistic curse of thinking that religions must be mutually exclusive. Still, he found the commitment I made in 2011 by being baptized a Christian quite puzzling. “Well,” my answer stumbled out, “by seeking to follow the example of Jesus with my whole heart, particularly through a kind of ongoing dialogue between ardent worship and the choices before me everyday, I’ve come to understand the creeds as pointers to the geography of life, with its horrors and its glories, manifested in the crucifixion and resurrection of Jesus Christ.” “That’s pretty abstract. Give me one specific example of how you have changed,” he demanded. “I’ve noticed that I cry a lot more easily,” I confessed. “Sometimes I weep just sitting in the pew and watching the acolyte prepare the candles, a reassurance that out of all the ugliness and misunderstandings of the human condition, the folks gathering for worship need, as I do, to recognize the sacred and align ourselves anew with the Power that gives us hope and life abundant. “Sometimes I am full of laughter as the service begins, but perhaps my eyes moisten when I see a parent and child taking communion at the altar rail — a fresh vision of the flow of generations, responding with varying degrees of illumination to the same call that Isaiah heard, in Chapter 6 of his book. “I’m not prescribing behavior for anyone else, just reporting that both in church and throughout the week, I seem closer to tears, a little less hard-boiled. I’ve a long way to go to emulate the love and compassion and embrace of Jesus; but however minute the improvement, I like myself better.” 2. Compassion Fatigue Still, when I saw the news about the gun slaughter at the gay Orlando night club, and again the attack at the place in the Istanbul airport where I have been, my first reaction was to shut down emotionally, just as I did immediately after Sandy Hook, Columbine, Charleston, Virginia Tech, and so many other shocks. No tears. “Well, what can we expect with the Supreme Court’s Second Amendment ruling?” the analyst in me said aloud in anger. I thought about the year when I was responsible for obtaining the names of those killed in gun violence in Kansas City each week, and how emotionally weary I became adding them to the prayer list. My first reaction to Orlando was disgust that so many political leaders seem to be owned by the N.R.A. even though the public favors measures to reduce our orgies of violence. As the news continued, I recognized my “compassion fatigue,” but God’s love never falters. God became human to suffer as we do. Finally I began to weep. There is so much to weep about, the refuge crisis,

the fires, the floods, the accidents, and the impaired health of those

we love. Usually I put these things out of mind. But sometimes I look at

the obituaries and see a young person I do not even know whose life has

been snuffed out, and I start to weep.

I’ve been puzzling why, from my new book, Thanks for Noticing: The Interpretation of Desire, one sonnet was the most popular in a contest with a score of racially diverse readers, young and old, gay and straight, professional and amateur, of several faiths, held at a Kansas City library for the 400th anniversary of Shakespeare’s death. While the sonnet is in perfect Shakespearean form, I don’t think it is my best. I don’t think it is particularly easy, either. No one has given me a plausible reason for its being selected most. But in thinking about the six presentations from my book this summer at St. Andrews and Grace and Holy Trinity Cathedral, I’m exploring one — possibly unconscious — dynamic that may explain its favored status. The sonnet may appear at first to be about a merely human love relationship gone sour. The speaker chooses to confine the love to a locket because it is so overwhelming, just as we, fatigued by compassion, sometimes shut down our feelings in order to get on with our lives. Then, in line 9, a forecast, using images from different faiths. The rapture in which the dead and living in Christ are “caught up in the clouds” to be eternally united in His kingdom is from 1 Thessalonians 4:17. In ancient Confucian thought, society would be set right by imitating the emperor honoring the gods by bowing to the South where they reside. In some Buddhist thought, the bodhisattva Maitreya is the future Buddha. Some Jews look for a Messiah who will establish the rule of Israel to bring peace to the world. All examples point to hope beyond the present distress, a desire that the mess of our world will be transformed. But the couplet, the last two lines, if read closely, though phrased in the future, subverts itself when we contemplate “God’s desire.” God offers us now both the cross and life abundant. That’s the package for this life, both to redeem the suffering around us and to take pleasure in God’s gifts. We can bring comfort to disaster. We can find joy in duty to the world. Ambrose of Milan wrote that we are simultaneously condemned and saved. Perhaps he meant that love brings both suffering and ecstasy. If we desire to know God, then choosing to love the world as it is, as God does, with all its evil, is, in a sense, our present salvation. Religious maturity is found in desiring to love as God loves. Julian of Norwich wrote that it is God who teaches us to desire, and that He is the reward of all true desiring, and that all shall be well. When the locket confining our love of the world melts, we are raptured, Maitraya stirs, the Emperors bow, Messiah comes; and then, in tears or laughter or quiet presence, our desire is released and the Glory of God appears. Love Locket This loud and too large love I have for you============================= Vern Barnet’s earlier book, edited with three others, is The Essential Guide to Religious Traditions and Spirituality for Health Care Providers.

<9> 2016 June, pages 8-9 "The Facts" vs "The Knowledge of God" The deepest knowledge cannot be put into words, but it can be lived.

1. Faith or Facts? The most important thing I tried to teach him is that religion is not a collection of facts; it is more an exploration of how to live one’s life well, with gratitude. This is why details such as when the Buddha was born or who wrote the Gospel of John are not essential to faith. While they can produce valuable insights, mere facts in themselves are not salvific. Instead it is the stories developed by the world’s spiritual traditions that lead to the sacred knowledge of how to live. Even a great secular novel or movie may contribute more to a life of faith than sorting factual claims into True and False columns, as my student wanted to do. Yes, our culture is woefully ignorant about the facts of the Christian tradition and other spiritual paths. Current political discussions make this appallingly evident. Knowing that Muhammad migrated from Mecca to Medina in 622, that Rosh Hashanah begins a Jewish New Year, and that the Vedas are the supreme scriptures in orthodox Hinduism are bits of knowledge that any American today might want to know. But knowing the story of Muhammad’s remarkable life and character, or the Hindu story in the Bhagavad Gita of how Arjuna resolves his perplexity when called to battle his own kin, or wrestling with the parables of Jesus—these may better serve to develop an appreciation for how one may live a life of integrity in the most trying of circumstances and cultural challenge. 2. Two Kinds of Knowing Thus there are two kinds of knowledge, knowing that, and knowing how—knowledge thatsomething is so and knowledge how something is done. I may knowthat Jesus was probably born in the year 4 BCE (Before the Common Era), but how Jesus’s life affects mine is more complicated, subtle, and substantive. I may know that a bicycle consists of two wheels on a frame, with propulsion and steering mechanisms, along with other parts such as brakes in a certain arrangement, but having that knowledge does not enable me to know how to ride a bicycle. One learns to ride a bicycle by riding a bicycle. Watching someone else may help. Knowing how to ride a bicycle is more like faith than fact. Although you can give directions to help someone learn how to ride, you cannot exactly tell someone else how to adjust each muscle to maintain balance as one senses the pull of gravity and the momentum of forward movement. The mechanism is like an arrangement of facts. The riding is more like an experience of faith. One learns to live worthily not so much by accumulating a set of facts but by practicing gratitude and service. One learns to follow Jesus not primarily from studying what may be facts, but by practicing the experience of Jesus in one’s life. A spirituality of pure reason is dead; spirituality is a breathing, deciding, helping, creating, loving way of living. A story may be a better road to faith than an assembly of evaluated facts in a logical structure such as my student desired. (Whew! Even that sentence reminds me he was a human being pretending to be a Christian robot. Once he collected all the facts, he would never have to struggle making decisions.) Stories reveal character. Aristotle defined character as what a person chooses and shuns. Our individual lives are too short for experiments of every kind, so we learn by imitating those whose lives are admirable and eschewing those whose folly leads to desolation. How did Jesus relate to the poor, the sick, the social outcast? How did Jesus answer “Who is my neighbor?” How did Jesus understand those who taunted him at his trial and crucifixion? The best concert reviewer or art critic cannot give you the experience of the music or the painting itself. The most scientific list of facts about a forest or the ocean or the mountains cannot explain the sense of wonder when you find yourself enveloped by such beauty. In “The Four Quartets,” Anglican poet T. S. Eliot wrote of such timeless moments and the impossibility of talk to match them: “Words strain,/ Crack and sometimes break, under the burden,/ Under the tension, slip, slide, perish,/ Decay with imprecision, will not stay in place,/ Will not stay still.” Our secular age shallows itself into tweets and outlines and numbers and passwords and distracted multi-tasking rather than exploring the heights and depths and breadths of what is too intense or too intimate or too majestic for words. 3. What We Can Know But Cannot Say Recent computer advances may clarify the distinction between what we know and can say, and what we know and cannot say. This is the difference between knowing that and knowing how, paralleling fact and faith. Do you know the game Go? It is an ancient board game far more complicated than chess. A computer beat a chess master in 1997 by sheer computing power. In 2011 a computer defeated Jeopardy champions by rapidly accessing facts and language patterns. There are more possible Go game sequences than atoms in the universe, too many for even the quickest computations to be useful. But earlier this year a computer won against an international champion. The computer was programmed not so much by facts but by examples, by what I’d call stories. It tested them repeatedly until it gained not information but skill. Just as a Go master cannot tell you how to be successful, the computer’s strategies cannot be reduced to facts or instructions. Michael Polanyi, a Twentieth Century polymath, famously observed “We know more than we can tell.” As a New York Times article put it, “no human can explain how to play Go at the highest levels. The top players, it turns out, can’t fully access their own knowledge about how they’re able to perform so well. This self-ignorance is common to many human abilities, from driving a car in traffic to recognizing a face.” This is why in sports and the arts, the best teachers are often those just under the highest levels; they can push their students to excellence, but the most accomplished athletes and artists cannot explain or transmit ultimate mastery. Baseball great Yogi Berra is reported asking, “How can you think and hit at the same time?” I may have helped my student collect significant facts, but even the greatest teacher could not have breathed into him the spirit of how to live with gratitude. As the course was ending, I mentioned that Jesus did not collect facts; he loved others. My student’s obsession with his columns of Fact and Fiction finally collapsed. They could not give him knowledge of God. He concluded that he himself was part of a story of a failed search. It was like thinking too much instead of trusting one’s balance, muscles, and sense of direction. He fell off the bike. The fall redirected his attention, he gained the skill of faith which he could not say, but which became part of his story; and he was grateful. I, too, have a sense of God, but I cannot tell how. Vern Barnet’s latest book is Thanks

for Noticing: The Interpretation of Desire. He previously wrote for

The Kansas City Star.

<8> 2016 April, pages 6-7 Work, Play, and Holy Living

The world is shot through with suffering and horror. It is also filled with beauty and love. Through Lent and Easter Day, we observed, practiced, and celebrated the reconciliation of such countering realities through the crucifixion and the resurrection of our Lord. Now through the six weeks of Easter we can strengthen our intentions with His grace. As Lent began, I had such thoughts when I assisted with a Godly Play class at the Cathedral. Julie Brogno, the teacher, produced a purple bag from which the children saw emerging first one irregular flat purple slab, then another puzzling shape, until six were united together to form a purple cross. After the children had a chance to recognize the unutterably “sad” meaning of the cross, the pieces were turned over. They were white, showing that the cross is also “wonderful,” for Jesus is still with us. Then the purple bag was turned inside out to reveal it is white on the inside, and the children hear, “Easter turns everything inside out and upside down.” The mystery of Easter was declared through play. 1. Play as Imagination We adults also do Godly play — through the liturgy. I don’t think I am being heretical in suggesting that we may apprehend divine mystery through play. Even the pre-Vatican Roman Catholic writer Romano Guardini presents worship as play: “The soul must learn to waste time for the sake of God, and . . . to play the divinely ordained game of the liturgy in liberty and beauty and holy joy before God” (The Spirit of the Liturgy, 1935). And the great scholar of play, Johan Huizinga, believed that “In the form and function of play, . . . man’s consciousness that he is embedded in a sacred order of things finds its first, highest, and holiest expression” (Homo Ludens, 1938/1949). Play grows from imagination. I cherish that warm summer afternoon when my son was three. We sat at the back yard picnic table, eating watermelon. My son finished his slice; only the rind was left. He looked up at the crescent moon in the sky and at the rind, and called it the moon. Then he changed his mind; now it was the smile of a Cheshire cat; finally it became a boat, “and I’m going to take it into the tub for my bath,” he announced. Think next of the client following a therapist’s suggestion to “place your deceased father in this chair and tell him how you feel.” We may justify this make-believe because the client may uncover truths about the relationship with the parent that otherwise might have gone unexplored. But that is looking at the play externally, from the therapist’s viewpoint, or from the client’s assessment after the fact. During the play itself, imagination is the engine of freedom which generates discovery. Now think of the arts. Let’s take poetry. William Blake asks, “Tyger, tyger, burning bright / In the forest of the night, / What immortal hand or eye / Could frame thy fearful symmetry?” We do not object; we do not say that no tiger, even one spelled tyger, can understand and answer him. But by imagination, even far removed and safe from any such beast, we are drawn to contemplate the ingenuity and majesty of the Creator. Perhaps the Anglican poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge best and most succinctly identifies the process by which art awakens in us that which is not present, or which we did not know was present, in his famous phrase, the “willing suspension of disbelief” (Biographia Literaria, 1817). [1] Imagination can be folly, but it can also lead us to deeper understanding of how the world works and to conceive of a better world, God’s kingdom. [2] 2. Play as Performance Two people in love gather their families and friends together and a priest presides in holy festivity. The couple are not married until the priest says, “I pronounce that they are wed to one another . . . .”* It is the performance of the words, “I pronounce,” that effects the new reality. This is not mere romance; it is a legal fact. In a liberal sense, marriage is gradual, preceding and following the ceremony; but it is the play of words that brings the new reality into focus and public recognition.[3] I do not know whether the ancients revered the performed word more than we do in our age of Twitter. They certainly knew that mere utterance of certain words actually performed the thing uttered, such “I confess” or “I welcome you” or “I warn you” or “I apologize” or “I promise” or when an authorized person says, “I baptize you.” The speaking of such words in context constitutes the act itself. And when for us the priest prays at the holy table that the gifts of bread and wine be sanctified to become for us the sacrament of Christ’s body and blood, God honors the performance of the rite’s words and transforms the Eucharistic elements into the bread of heaven and the cup of salvation. [4] 3. Play as Work With performatory language the world began. God said, “Let there be light,” and there was light. Could the ancients who gave us the Scripture imagine a more magisterial way of expressing the power of the word divinely spoken? And in our own age of science, is there a more beautiful way of proclaiming how, after some 15 billion years, we have our being in the cosmic drama? Merely by speaking the world came to be. A composer of music plays with sounds in time, a painter plays with shapes and colors, an actor plays with character and presence. Their imagination produces works of art. Play is an activity whose meaning is intrinsic; it justifies itself. My son took his watermelon rind boat into the tub simply to enjoy it. We listen to music simply for pleasure, without any further purpose — unless we do it for pay or some other external reason, when it is also work, which is activity for a purpose outside of the activity itself. The writers of Exodus (20:11) [5] explain the Sabbath by citing God’s rest from work on the seventh day, Like them, we often see work and play as opposites. The Sabbath is holy, for one puts aside labors done for ends beyond themselves. The Sabbath is play; the liturgy is play; what is holy needs no justification beyond itself. But if we are to be like children (Luke 18:16), can we find our work is actually play? If we take pleasure our work and find meaning simply in performing it, every day becomes a Sabbath. In divine mystery, the pieces of work and play are turned inside out and upside down. When offered as praise to God, even the most menial labor is sanctified as vocation. Our hymn by George Herbert offers such sacrifice of praise “seven whole days, not one in seven” (The Hymnal 1982, 382). In Godly Play, the pieces of the cross, purple and white, sadness and exaltation, are emblems of our own lives of suffering and joy. When we dedicate our work to God, doing our best but leaving its fruition to His hands, as Jesus yielded to the Father on the cross, we turn work to play, and play is holy living. Vern Barnet’s latest book is Thanks for Noticing: The Interpretation of Desire. He previously wrote for The Kansas City Star. *The Celebration

and Blessing of a Marriage 2 - The Episcopal Church

[1] Think of the fictional novels and films that stir our souls. We even treasure Aesop’s fables such as “The Ant and the Grasshopper,” with creatures that speak. The suspension of disbelief provides the evidence for things not seen. [2] Perhaps the writer who described faith as “the substance of things hoped for, the evidence of things not seen” (Hebrews 11:1) teaches us about the place of sacred imagination in our lives. The play of such imagination can change the way we see reality and how we live our lives. [3] It is not the certificate that creates the marriage; it is the words in the occasion; the certificate with the witness signatures is merely the documentary proof. [4] Of course this description does not begin to unwrap the mysteries of understanding Holy Communion, but it shows how performatory language plays in our awareness of God’s grace. [5] The writers of Exodus (20:11), unlike those of Deuteronomy (5:15) . . . . <7> 2016 January, pages 6 and 7 Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. — A Christian and Planetary Prophet A personal appreciation of America’s great prophet and martyr of non-violence

In 1968, when I was a graduate student at the University of Chicago, I was invited to preach in Bloomington, Illinois, on Palm Sunday, April 7. By late March, I had completed my manuscript. Then Martin Luther King, Jr. was assassinated April 4. I threw out what I had written and started afresh, and wrote that I had met King earlier that year in Washington, D.C,, where he renewed his controversial opposition to the Vietnam War. I still remember that meeting in a church basement with a chill. He was late, very late, in arriving. My group learned that threats on his life were serious. I concluded my new sermon by saying that “King’s death may bring our nation out of the winter of racial injustice. Like Christ, he was wounded because of our sin” as a nation. Obviously our nation is still in winter, in need of confession and redemption. King, whose holiday we observed in January, is a central figure in the American story. Here let me propose in three parts why he is also central prophet in planetary religious history. 1. A World-Wide History of Non-Violence When King was 6 years old, Mohandas Gandhi, a Hindu who helped India to gain independence for India from the British raj, said, “It may be through the Negroes that the unadulterated message of non-violence will be delivered to the world.” In tracing this history, we discover the irony that Gandhi himself claimed his Hinduism only after being stirred by the writings of a Russian Christian, Leo Tolstoy, who, because of a personal crisis, was drawn to the Sermon on the Mount and the Gospel of Love. As the Harvard scholar Wilfred Cantwell Smith has shown, Tolstoy himself was converted to non-violence and social service by the Christian story of Barlaam and Josaphat, a retelling of an earlier story from a Muslim source, which in turn received it from the Manichees, who had recast the story of the Buddha, successively called Bodisaf, Yudasaf, and Josaphat. And earlier versions suggest Jain or other beginnings. Just as Gandhi matured in Hinduism by discovering Christianity, King was strengthened in Christian love by respectful study of the Hindu. King kept a photo of Mohandas Gandhi above his desk. King adapted Gandhi’s satyagraha, the “truth-force” that Gandhi developed. Here In outline are principles they shared: (1) Cowardice is the worst possible position. We

can never have all the information we might want before we need to act.

(2) Some situations demand that we suffer as individuals to achieve freedom

for all. (3) We must start at home, with ourselves. We can authentically

urge change upon others only to the extent that our own spirits are orderly.

(4) We must find humanity in our adversaries and beware of demonic potential

within ourselves. (5) While confrontation may be necessary, cherishing

the personhood of all involved in the conflict may lead to a creativity

beyond what we can presently see.

2. The Letter from the Birmingham Jail Every year I read the letter King wrote from jail in Birmingham. It is a check on my own claim to spiritual commitment and service. King’s approach to the white ministers who complain he is an “outside agitator” is a model of frank disagreement presented in love. They want him to wait for justice. He responds “Justice too long delayed is justice denied” and reminds them that he is “in Birmingham because injustice is here. Just as the eighth century prophets left their little villages and carried their ‘thus saith the Lord’ far beyond the boundaries of their home towns; and just as the Apostle Paul left his little village of Tarsus and carried the gospel of Jesus Christ to practically every hamlet and city of the Graeco-Roman world,” he too is “compelled to carry the gospel of freedom beyond” his “particular home town.” In the darkness of his cell, writing on scraps of paper, to make his case he cites Socrates, Tillich, Aquinas, Martin Luther, John Bunyan, T. S. Eliot and, most importantly, the scriptures. In the letter, King outlines four stages of a non-violent campaign: (1) the collection of the facts to determine whether injustices exist, (2) negotiation to redress injustice, and when correction is not forthcoming, (3) deliberate self-purification, and (4) direct action. The “means we use must be as pure as the ends we seek.” This is why those engaged in direct action were repeatedly asked, “Are you able to accept blows without retaliating? Are you able to endure the ordeals of jail?” and so forth, emulating the apostles and Jesus himself. Some have proposed that the Letter from the Birmingham Jail ranks with the epistles of Paul and should be admitted into the New Testament canon. 3. King’s Last Sermon On March 31, 1968, the Sunday before he was assassinated, King preached at the Washington National Cathedral. You can hear a recording by searching on YouTube by his sermon title, “Remaining Awake Through a Great Revolution.” In that national seat of our Episcopal tradition, King quoted the great 17th Century Anglican preacher and Dean of St Paul’s Cathedral in London, John Donne whose famous words, “No man is an island of itself. Every man is a piece of the continent, a part of the main.” King used Donne to summarize his point that “We are tied together in the single garment of destiny, caught in an inescapable network of mutuality. And whatever affects one directly affects all indirectly. . . . This is the way God’s universe is made . . . .” Today these words, in our time of increasing social fragmentation and inequality, might well chastise us and bring us back to a vision of what God wants for us. “We are challenged to develop a world perspective. No individual can live alone, no nation can live alone, and anyone who feels that he can is sleeping through a revolution.” Even then, before the internet, King saw that the world geographically is interconnected. He said that the challenge is to make the world one “in terms of brotherhood.” King’s sermon was optimistic. His texts were two passages from Revelation, “former things are passed away” and “behold, I make all things new.” He paraphrases the 19th Century preacher Theodore Parker so well we now identify the words with King himself: “The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice.” Beyond race and class and every other human category,

King’s prophethood, rooted in the Christian faith, speaks to all people

everywhere. The youngest recipient of the Nobel Peace Prize, he is memorialized

across the globe in many places, including, fittingly, the Gandhi King

Plaza in New Delhi. His words and his martyrdom challenge us to find today’s

ways of fulfilling our baptismal promise throughout the “inescapable network

of mutuality,” bending toward justice.

Vern Barnet‘s latest book is Thanks

for Noticing: The Interpretation of Desire. He previously wrote for

The Kansas City Star.

<6>

This year, before Thanksgiving. even before Halloween, earlier than ever in October, artificial Christmas trees were on sale. To those who wish to put Christ back in Christmas, one wag wearily desired merely that Christmas be put back in December. It is true that in Eternity, all is whole, a mysterious and wondrous completeness; but in the human sphere of time, we do best to honor this mystery as a story told in a sequence through which we enter a better understanding of Eternal Love brought into the field of time. 1. Preparation That sequence, the liturgical year, begins with Advent, and it is a time of preparation. A classic issue in Buddhism is whether you can prepare for Enlightenment, vaguely parallel to the Christian tension between formation and conversion. On my first trip to Japan, I determined to get an answer, or at least weigh the arguments on each side, no matter how complicated or esoteric. In checking in at the Shingon sect headquarters at Mount Koya, I requested an audience with the chief priest to put this problem before him. The manager said I had better to count the petals on a lotus bloom than put any question to the chief priest. I persisted, and before I was settled, the priest appeared. Anticipating a long and difficult philosophical disquisition, I asked, “Is Enlightenment sudden or gradual?” He responded matter-of-factly, “Enlightenment is sudden, with gradual preparation.” Problem solved. Although I am skeptical about Malcolm Gladwell’s position that takes roughly ten thousand hours of practice to achieve mastery in a field, I know that it was only after persistent study of Chinese art, when at times I felt that I would never get it, that I woke up one morning, looked out the window, and suddenly saw the world as a Sung Dynasty painter might have seen it. I prize spontaneity and surprise, but their delights are more likely when things are settled enough so the unexpected can be enjoyed. I recently talked with a young father who told me about the preparations he and his wife had made before the child’s birth. The preparations did not diminish their joy; rather it gave them a freedom from distractions (what shall we do about diapers?) by having everything in place. They become one with the moment, to discover what they prepared for but could not have anticipated. A more ordinary example: You belong to a book discussion group. If you have not read the book, you may still enjoy the conversation, but it probably will not make as much sense as if you had prepared by reading the book. Advent is a way of recognizing that something special is going to happen. Our very preparation may make us more ready to be touched in a way we could not have planned by readying our attention. 2. Two Stories Matthew tells us that Joseph dreamt that Mary would bear a child who would “save his people from their sins.” Magi from the East journeyed because a star foretold his birth, which would take place, according to the prophets, in Bethlehem. Luke tells of the Annunciation and other signs and prophesies. Similar motifs are found in stories of other religious figures. For example, Deacon Jerry Grahber’s centering prayer groups at Grace and Holy Trinity Cathedral have been studying “Jesus and Buddha: Paths to Awakening” from the Center for Action and Contemplation, which includes James Finley’s comparisons between our Savior and the Buddha. I asked the Most Ven. Sunyananda Dharma, Patriarch of the United Buddhist Church, to tell me the birth story of the Buddha. I knew that like Joseph, the Buddha’s father had a dream. Both the mothers traveled before giving birth. You may discover other similarities and differences in the stories. Here I summarize Dharma’s account. Once the King presided over a festival during which his wife, Queen Maya, tired. She dreamt that heavenly beings carried her into the skies. Soon a white bull elephant appeared, clutching a white lotus in its trunk. The elephant circled Queen Maya three times, when he then placed his trunk holding the white lotus into her womb. When the queen awoke, she related the dream to her husband, who summoned sixty-four Brahmin priests to interpret the dream. They said that Queen Maya was to bear a child who, if he were shielded from the difficulties of life, be would become a great ruler like his father. However if he were exposed to suffering, he would become a mendicant priest and sage. Queen Maya did indeed conceive a son. As she was about to deliver, she traveled, carried on a palanquin and accompanied by 1000 servants, to a place where she would be more comfortable giving birth. Arriving in Lumbini garden, the Queen descended her palanquin and, grasping a branch of a tree, gave birth effortlessly to her child. He immediately took seven steps, leaving in his wake lotus blossoms springing up at his footprints, and spoke, identifying himself as world savior. Dharma added, “Elements of the story such as the white elephant were valued in Vedic culture and many aspects of the story are retold from Hindu mythology.” 3. A Birth Just as we have different stories of preparation for Christ’s Nativity, so many versions of the Buddha’s birth are told. The teachings of Jesus and of the Buddha are similar, but I have always been impressed by their different birth and life stories. Jesus was born in a manger, the Buddha in luxury; Joseph was a carpenter. the Buddha’s father was the king. Jesus lived a simple life; the Buddha grew up in palaces and pleasure until he discovered others suffered and abandoned his princely sway to find out why. When Jesus was perhaps 33, he was crucified in a social and political drama and his disciples deserted him: the Buddha died at age 80, perhaps from food poisoning, in the care of his beloved companions. God entered the realm of time to became human in Jesus; in Buddhism, the prince accepted the human condition by abandoning his palaces. Finley argues that both Jesus and the Buddha taught that our problem is ignorance. Finley cites the prayer of Jesus on the cross: “Father, forgive them for they know not what they do.” I suppose the Buddha’s teaching that our troubles arise from unhealthy attachments is a kind of ignorance, but I think the similarities and differences are both important. The history of science includes accounts of accidental discoveries made by those in pursuit of a solution to a problem, with an unexpected and valued result. Such pursuit is a kind of departure from ordinary thinking, the known landscape, a metaphorical journey into an unknown country where one is prepared for a startling revelation. Preparation cannot compel such a manifestation, and a wonder may appear without intentional readiness. Still there is no better way to honor and welcome

the new birth of the holy within our hearts than by preparation. “Eternity

is in love with the productions of Time,” wrote mystic Christian poet William

Blake. In our observing Advent, we may prepare ourselves for a fresh glimpse

of how God’s eternal and saving love comes to us in the unexpected manger,

in history, and in our hearts.

<5> 2015 October, pages 6-7 Views from the Outside, Inside, and Center

Usually, if my birthday falls on a weekday, I go to the noon service at the Cathedral. But this year my birthday fell on Memorial Day and the Cathedral was closed. So I decided on a different spiritual discipline. I chose an outside path; but later, in a surprise, I got an interior perspective. I like seeing controversies when folks on both sides are well-meaning. 1. An outside view

That morning I walked about ten miles from the former Kansas City Bendix/AlliedSignal plant on Bannister (95th Street), just east of Troost, to the new facility at 14520 Botts Road. Now called Honeywell, this plant produces 85 percent of the non-nuclear material used in our nuclear bomb arsenal. I joined about three dozen protesters organized by PeaceWorks-Kansas City. They ranged from 20-somethings to those of us in our 70s. Much of the time I walked with Tom Fox, publisher of the National Catholic Reporter, who carried a large American flag. I asked: How can peace prevail when our resources perpetuate the overwhelming and unnecessary size of U.S. nuclear armaments? The question was especially sharp for me this year, the 70th anniversary of our controversial bombings of Japan. The father of a Konkokyo Shinto priest who was my roommate in seminary was killed in the Hiroshima blast. When I visited that site, I was seared by how that single bomb, now a midget weapon, killed and make living hell. Tom had reported that in 1983, U.S. Roman Catholic bishops offered “strictly conditional” moral recognition for nuclear deterrence only with a “resolute determination to pursue arms control and disarmament.” Then the U.S. and Soviets possessed more than 60,000 such weapons. For some years after, reductions on both sides were made. But the process has stalled. In 2009, the 76th General Convention of the Episcopal Church asked policy makers “to determine a timely process for the dismantling of existing U.S. nuclear weapons while urging other countries to do likewise . . . .” Other religious groups have made similar judgments. Now estimated between 16,000 to 22,000, these weapons seem morally unusable. They are homocidal and ecocidal. We keep updating them, with a trillion dollars scheduled for our arsenal in the next 30 years. The Honeywell plant itself cost nearly a billion dollars. When we arrived near the Honeywell plant, guards politely reminded us we could not step past the purple line in the road to approach the building. They offered us bottles of water. 2. An inside view Surprise. As an alum of the Civic Council’s leadership training program, I was invited to tour inside Honeywell with fellow alums June 11. A few weeks earlier I could not step onto the grounds. Now I was cleared through security, given a badge, briefed on the plant and its purpose by the officials, and shown wondrous equipment — and a storeroom with 800 million dollars of stuff. The employees said their work promoted peace by making sure that the weapons they serviced would work, maintaining a credible response against aggression. It would be too easy to dismiss the place — with machinery so heavy a concrete floor was four feet thick with 27 piers into bedrock, and so delicate one screw-driver’s blade is one-tenth the width of a human hair — simply as toys for boys. The tour guides were sincere, honest, and forthright in answering questions. I honor those who argue that, given today’s realities, we must be able to deter those who might otherwise seek to harm us. Still, I couldn’t help being perplexed that so much ingenuity is brought to weapons of death and so little to supporting conditions for peace. 3. A centering view My interest in nuclear disarmament is not new. In 1963 I wrote to Lord Bertrand Russell. His letter began with an apology for his delay in responding. I think he had been jailed for one of his protests. He wrote with pessimism about a future without a “movement of mass resistance by ordinary people determined to prevent the militarists and politicians from allowing their murderous weapons to be used.” But 70 years have passed since the bomb was used. And we have so many other problems about which to worry. How can we get a perspective on all of them at once? Issues like over-reliance on sheer military power arise because our sense of the sacred is scattered and we are sick. Our spiritual disease presents three general symptoms: our environmental crisis, the uncertainties of personhood, and poorly covenanted communities and nations. The cures for the profanation of nature, selfhood, and community are proclaimed by the world’s faiths. They are a spiritual GPS directing us to the holy center we must find — as the mystics say — everywhere. The primal faiths (American Indian and tribal African ways, for example) inculcate ecological awe, for nature is to be respected more than controlled. Nature is a process which includes us, not a product external to us to be used or disposed of. A centered, sacred attitude toward nature is wonder, not consumption. Asian religions (such as Hinduism and Buddhism) describe the center as genuine personhood when our actions proceed spontaneously and responsibly from duty and compassion, without ultimate attachment to their results. In the monotheistic traditions (including Judaism, Christianity, and Islam), the awesome work of God is manifest in history’s flow toward peace and justice when peoples are governed less by profit and winning and more by the covenant of service. Mere summaries of these three antidotes to our desecrated world cannot replace the hard work of those seeking better schools, moderating climate change, reasonable gun control, reversing economic disparity, eliminating date rape, halting the death penalty, ending racism, or reducing nuclear arms to zero. But work on any one problem can help cure others because they are all interrelated. Work on whatever issue grabs you. I’m not smart enough to set your priorities. Except, must we not remember that the evils we face all arise from a fragmented, broken perspective, bereft of the transcendent? In whatever way God uses us in redemptive work, we may be less likely to sin ourselves if our specific commitments open us, rather than blind us, to the holy network in which others also toil. The insights of each faith may be latent in all others. Still, Christians perhaps have a special responsibility to uplift the wisdom from all faiths because we comprise the largest tradition on the planet; and, at this point in history, we have developed what may be the most effective methods learning from other faiths while retaining the integrity of our own. Perhaps no form of Christianity is better outfitted to do this than the Episcopalian. Our tradition of embracing all peoples and multiple approaches toward the sacred becomes a model method for profound interfaith exchange. For me that model is vivid in the sacraments. They fuse and transcend nature, personhood, and community. Look! The water of baptism and the bread and wine of the Eucharist are gifts from nature. In them we find Christ, God incarnate as a person, our exemplar. And through the sacraments we become the Body of Christ, the beloved community. Thus it seemed my birthday

walk was not only a protest but also a pilgrimage toward the center.