|

917.

120411

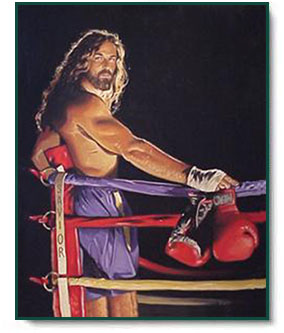

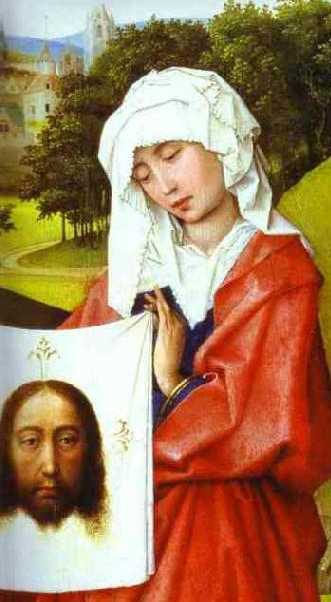

Email "Interview" with Dr Morgan Q1. BARNET: When I read the following description of your talk, two perplexing images immediately came to mind. "The Likeness of Jesus." --Embedded in our minds, whether we are Christian or not, are images of Jesus that strongly predispose us to assume that we know what he looked like. We recognize versions of these quite easily, and when we think about who he was and what he meant, we automatically call up these images, which intermingle with our ideas, shaping them in important ways. Professor Morgan will explore in his illustrated presentation the history and characteristics of visual thinking about Jesus, exploring what “likeness” is and why it matters, how religion happens visually in the instance of Christian imagination, and how conceptions of Jesus have come to be challenged by alternate visual treatments of his appearance.

The first image is an icon of Christ described by Nicholas of Cusa in his

mystical "The Vision of God" in which the fixed eyes seem to follow the

viewer wherever the viewer stands to view the image. of Christ is fixed

and unmoved. In Chapter VI, Cusa writes "that face which is of the true

type of all faces hath not quantity. Wherefore it is neither greater nor

less than others, and yet 'tis not equal to any other; since it hath not

quantity, but 'tis absolute, and exalted above all." The second image is

of Stephen S Sawyer's pugilistic painting of Jesus, "Undefeated." I'll

insert the image here.

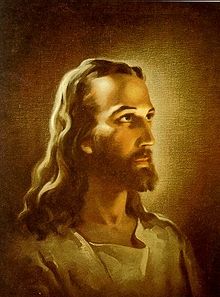

A1. MORGAN: I am familiar with both images, and in my latest book, The Embodied Eye: Religious Visual Culture and the Social Life of Feeling (University of California Press, 2012) I even wrote about Nicholas of Cusa's text and the Veil of Veronica image by Rogier van der Weyden that inspired his fascinating discussion. Both images seek a direct relationship with the viewer, one that will make the viewer feel addressed by Jesus, individually or personally but also collectively addressed. The images hail a response--from the individual and from the group. These images look first in order that viewers will return the look. This is one powerful form of visual piety because it touches the individual and it knits together the group that responds in kind, together. Evangelicals will understand the individual colloquy with the image as a "personal relationship with Jesus." But it's much older than modern Evangelicalism. It goes back to the late medieval spiritual ideal of "imitatio christi" and even further than that to the earliest history of icons. The Veronica is a legend about an image taken directly from Jesus' face as he marched to Calvary to be executed. He was in the midst of his passion, his suffering, and it was at that point that he sought a direct encounter with the viewer through the image. That image marks one of the powerful moments in which Christians sought to imitate Jesus, to be like him, to share his suffering in order to endure their own suffering in a Christ-like manner. This is a Latin Christian idea, one that prevailed in western Christianity. In the East, the likeness of Jesus was linked theologically to the incarnation and to the liturgical context of worship and devotional life. Jesus was the summit of the intercessional apparatus of salvation that his life and death put in place, and he appeared with icons of Mary and the saints in churches, shrines, and homes to enable the sacramental means of salvation and sanctification that structured the lives of those seeking holiness. The direct gaze of icons, Jesus and all of the saints, meant their presence made available in prayer and worship for the sake of the faithful. Stephen Sawyer's image addresses viewers not only with his gaze, but with his body. In contrast to most icons and devotional images like Van der Weyden's Veronica, Sawyer's Jesus is macho. He flexes his arms to proudly display his musculature, perhaps to address viewers in a way that assures them of his machismo. People want different kinds of Jesus, so his likeness varies, depending on who is doing the looking. Sawyer's Jesus seeks out those for whom masculinity is a primary feature of their connection to Jesus. For others, who don't want that, this image probably looks silly. Q2. Twenty-five hundred years ago Xenophanes wrote to the effect that Ethiopians say their gods are snub-nosed and black, Thracians that theirs are blue-eyed and red-haired, and that if horses could draw, their gods would look like horses. At the back of our minds we know this. But why do many of us persist in carrying images of Jesus that affect us even when we know the images are inaccurate? Can we benefit by seeing many images of Jesus from various ages and cultures? A2. People want to see the likeness of the Jesus who is like them. Likeness is about more than appearance. It is about the relationship between who is seeing and who is being seen. So the Greek philosopher shrewdly pointed out that human beings tend to see gods who resemble themselves. Is that because humans are narcissistic and narrow-minded by nature? Not necessarily. It's because people seek out a relationship with their deities. They want to be like them, and that means that deities can often appear like those who image them. Likeness discerns a mode of connection, an affinity that brings parties together and helps to keep them together. The relationship might easily become narcissistic, ethnocentric, even racist. Or what theologians call "idolatrous," which means substituting a symbol or image or object for what is hailed, discerned, and encountered in an artifact, but not limited to it. The value of looking at many different portrayals of a god or an ideal or a goal in life is very clear: by seeing it in different forms one is able to evaluate more dispassionately what the nature of one's relationship is and what vital differences may or ought to exist between what we want and what we need. Q3. The Sawyer image contrasts (for me, at least) with the more familiar Warner Sallman's portrait of Jesus. I've also seen Jesus as a woman. Can you give some examples of alternate images of Jesus and why they might be important? A3. Warner Sallman's Jesus is much closer to the traditional conception of Jesus as a slender, humble, meek character. Sallman intended to portray Jesus submitting to his father's will to go to Jerusalem and undertake the arduous work of suffering and death. So he looks quietly upward in an act of solemn acknowledgment of his father's bidding. The thinness and non-macho character of this Jesus was meant to signal that he did not belong to this world, did not prize achievement, food, drink, fine clothing, comfort, reputation, or worldly success, but pursued the non-material aim of his mission to do God's will. Many images of Jesus today seek to portray him in a very different way. Sawyer and many others craft pictures that will appeal to viewers by presenting a Jesus who makes them proud. They want a hero, a man of whom they are proud, a man capable of suffering in a mighty way. A hero figure who fights hard and cuts a sleek, impressive figure. Many Christians in the US today feel that their faith has taken it on the chin in a nation which they believe was once Christian but has since abandoned the faith and even come to disrespect Christianity. They feel their faith is under siege. So they want a Jesus who fights back. A guy who does not take disrespect by appearing humble or meek. You don't have to look far to find anger among conservative Christians, Catholic or Protestant. They resent what they believe is contempt for their faith, and they look to a Jesus who will vindicate their cause. Others search for a different alternative. Some feel that all the male Jesus figures miss half of Christendom's faithful--women. And they feel that the excessively masculine Jesus warps the faith and needs badly to be corrected by visual explorations of neglected aspects of Jesus' character. They want a Jesus who is like something different than anger and pride and machismo. Perhaps the most memorable recent image is Janet McKenzie's "Jesus of the People," which won the National Catholic Reporter's 1999 contest for the Jesus of the New Millennium. McKenzie used an African-American woman as a model and ignored the ancient visual formula for portraying Jesus. When you first see the image she produced, you may not recognize it as Jesus. But it's a fascinating experiment in likeness. It helps one realize what constitutes "likeness." Q4. Although Islamic art has portrayed Muhammad, in most cultures Islam has prohibited such images even though Muhammad is not considered divine. Do you think that Muslims benefit by eschewing images of Muhammad? 4. Muslims practice enormous respect for Muhammad, and they have produced images of him over their long and varied history. But in the Sunni tradition in the last several centuries, the practice of refusing to produce visual images of him has prevailed. In other traditions of the faith, Sufism and Shi'ism, for example, there is much less anxiety and a greater use of images generally. As a scholar of religious images, I wonder if we won't see fascinating innovations as Islam becomes rooted and pervasive in North America and Europe and far beyond, say in Latin America, for example. Religions must compete for adherents in the marketplace of culture, and that means that no religion ever stays the same. I would not be surprised if Muslims one day found that images of the Prophet became helpful in image-laden cultures such as the United States and Latin America. Not to be worshiped, but to display them as advertising or as instructional illustrations, as political totems, as icons of group identity. After all, when your children are being bombarded by television and internet images all day long, using fire to fight fire becomes a very compelling tactic in safeguarding their formation. David Morgan,

The title of the talk is "The Likeness of Jesus." Embedded in our minds, whether we are Christian or not, are images of Jesus that strongly predispose us to assume that we know what he looked like. We recognize versions of these quite easily, and when we think about who he was and what he meant, we automatically call up these images, which intermingle with our ideas, shaping them in important ways. Professor Morgan will explore in his illustrated presentation the history and characteristics of visual thinking about Jesus, exploring what “likeness” is and why it matters, how religion happens visually in the instance of Christian imagination, and how conceptions of Jesus have come to be challenged by alternate visual treatments of his appearance. 7:30 PM, Monday,

April 16

From David Morgan's Website: David Morgan is Professor of Religion with a secondary appointment in the Department of Art, Art History, and Visual Studies at Duke. He received his Ph.D. at the University of Chicago in 1990. He has published several books and dozens of essays on the history of religious visual culture, on art history and critical theory, and on religion and media. His most recent book is The Lure of Images: A History of Religion and Visual Media in America (Routledge, 2007). He edited and contributed to Key Words in Religion, Media, and Culture (Routledge, 2008). Earlier works include Visual Piety (University of California Press, 1998), Protestants and Pictures (Oxford, 1999), and The Sacred Gaze ( California, 2005). Morgan is co-founder and co-editor of the international scholarly journal, Material Religion, and co-editor of a book series at Routledge entitled “Religion, Media, and Culture.” |

Stephen

Sawyer

Stephen

Sawyer

Warner

Sallman

Warner

Sallman

detail,

detail,

Janet

McKenzie

Janet

McKenzie